Today we’re going to spin a yarn about three seemingly unrelated events: The steady shift of investment money from active investment products to passive investment products, sales practices in Canadian banks, and the recent anti-trust settlement regarding realtor commissions. You might look at this with bemusement. “What does this have to do with me?” And fair enough for our non-Canadian, non-investment-selecting, and non-Realtor readers. But even for those with at least one foot in this particular pool –and trust me, it’s more of you than you think—all of these things affect you on an ongoing basis. So today, let’s talk about the good caused by disruption and differentiation and how it benefits you on a daily basis.

Of Disruption – Active vs. Passive

Investment products as we know them now came about in the early 20th century with the passage of a battery of laws designed to give shape and form to capital markets, and most importantly, to protect investors from being so easily ripped off by unscrupulous con men selling bad investments. At the time, investment products were effectively and universally what we’d call “active.” This means products that are professionally managed. Imagine almost any movie you’ve seen about hedge funds or wall street people, where they stare closely at fancy charts with green and red lines, eyeballing the marketplace for the sweet opportunity that will make them and their clients a fortune. These are teams of well-paid and highly educated professionals, whose pedigree is only outweighed by the size of their bonus checks for all the money they make in managing millions if not billions of dollars on behalf of their clients. We even pay them some proper respect with an illustration in our conference room.

Yet, despite the homage paid by the illustration, there is an uncomfortable truth: statistically speaking, these beknighted professionals are bad at their jobs. It’s not that they don’t make money for their clients, it’s that they don’t make more money for their clients, particularly with respect to the question of whether they produce enough extra money for their clients to offset their compensation.

This was the observation of John Bogle back in 1975 when he launched the First Investment Trust, which later became the Vanguard S&P 500 fund. His argument at the time, which has been magnified to the point of comparison to the ten commandments, was that no matter how hard they tried, the active investment professionals could not consistently produce enough value to warrant their extra compensation, and that as a result, the average investor would be better off buying the cheapest investment that tracked the benchmark index of interest the most closely over the long term. Since then, the evidence is pretty clear: He was right.

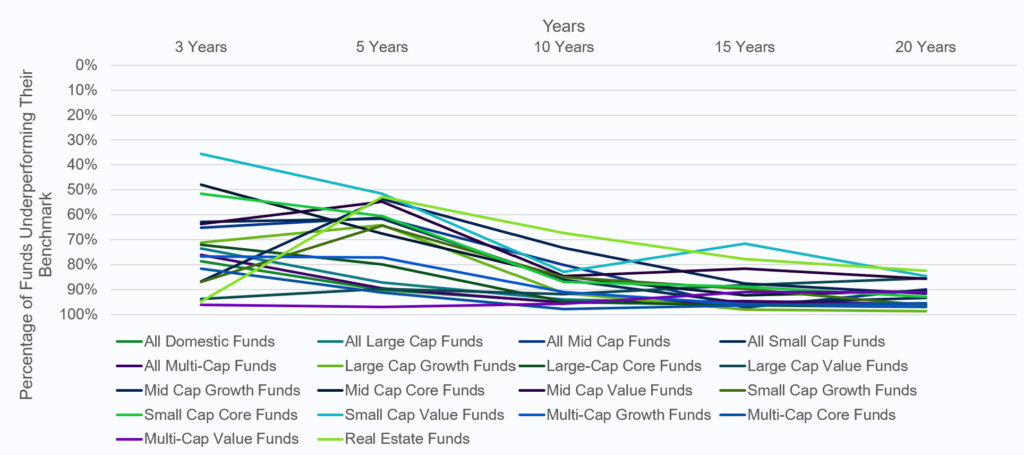

Data from S&P Global Indices versus Active (SPIVA) Research, 12-31-2023.

The chart above shows the number of investment managers who are underperforming their investment product’s benchmark index year over year. Some categories are a bit better than a coinflip in the short term (looking at you, small cap value funds) but as time goes on, inevitably the active managers fail to consistently outperform, and so in most categories only 1 in 20 or 1 in 25 funds are still outperforming after two decades, and even in the “best” categories, it’s little better than 1 in 5. Now of course, by the power of hindsight we can see who the winners and losers are, but if we hop in the time machine to 2024, we have no idea which managers in which categories are going to outperform; even worse, even if they’re outperforming their benchmark, the actual investment category itself might simply have poor performance.

The revolution in this arena over the past several decades has finally come to a head almost 50 years after the advent of the passive index fund. As of January of 2024, there is more money in passive mutual funds and products than their active counterparts: $13.3 trillion to $13.2 trillion dollars. As the evidence has mounted year after year, decade after decade, that passive has better long term performance than the average active fund, competition in the passive marketplace has steadily driven costs down, with many active products charging easily ten to fifty times as much as their passive counterparts, while delivering less consistent and lower returns. The value of this innovation has been clear: not only have returns in the past decade been some of the best in history, but consumers have attained these returns largely (though not solely) in part to the money they’ve saved by not overpaying for the pedigree of active managers.

As a firm, MY Wealth Planners has ridden this wave. As the first fee only financial planning firm in Longmont, we started from day one with an emphasis on passive investment products in our client’s portfolios, and consequently, have ridden the rails with the market, knowing that our contribution to investment returns for our clients isn’t from unique insights or deep research, but by accepting that the market itself is the best driver of outcomes, and simply clinging as closely to it as we can, and as best suits our clients individually. Yet, you were promised a parable that relates the topic of active and passive to bank sales and real estate commissions. How does this all tie in?

To Sell is Human…

…and let’s be honest, humans are kind of gross. With due deference to Daniel Pink’s best selling title, the drive to be better and provide better outcomes for others is a uniquely human trait. We hear every day about people who commit their time and energy to the betterment of others, whether by volunteering or through constant innovation and striving in private enterprise. We have technology, medicine, and a standard of living that would look like the lifestyle of the gods to anyone even a hundred years ago. “Indoor plumbing, heating in the winter and AC in the summer, and all the knowledge in the world at your fingertips via a small box in your pocket?!” One might say.

Yet, not all striving and enthusiasm for “better” is good. Particularly when conflicts of interest play into it. Over the weekend, CBC Canada Radio released an expose from an undercover investigation of banking behaviors in Canada; specifically, the sales practices of their tellers and financial advisors. With hidden cameras, reporters went into banks and asked for basic financial advice and recommendations, and without fail, almost every teller and advisor they spoke to tried to sell them products they didn’t need, misled them, or outright lied to them. Worse, it was observed that many of them simply didn’t seem to know the answers to the questions they were asked, but were instead simply saying whatever they could to get the undercover reporters to purchase a product or sign on the dotted line.

Sitting here in Longmont Colorado, you might say that’s all well and good, but that was Canada. We do things better here than those Cannucks, eh? Well, regretfully, no, we don’t. While the United States has a patchwork of financial licensing regulation and concurrent marketing and sales regulation, financial planners and advisers in Canada are more heavily regulated than we are in the United States. And though I’m not about to put on a wig and mystery shop the local BOA and Wells branches, I think that even if we went to our local credit union, we might find that many of the people working the teller lines and even the smart-looking men and women in the financial advisor’s offices are simply trying to sell us something. I’d know, I have personal experience with that one.

The simple fact of the matter is that while the Canadian Finance Ministry and our regulators here in the United States would make a big show of telling us how seriously they take protecting consumers from bad actors, they simply haven’t the bandwidth. There are not enough lawyers in the SEC, FINRA, the State Securities Regulators, and even the state Insurance Commissioners to stop people with bad motivations from selling people bad products or giving them financial advice. Sadly, even self-regulation by organizations like the CFP Board tend to be reactive rather than proactive. We can only shame or punish people after the harm has been done, rather than create such a stringent set of disincentives to stop people from performing poor behaviors. While the public has gotten more educated over time about the importance of working with CFP Professionals and financial planners who have less conflicts of interest (none of us have none, sorry), the vast majority of consumers working with financial professionals today are still doing so with people whose incentives are not always closely aligned with theirs, and no degree of regulation is going to fix human nature.

The simple fact of the matter is, much of the best regulation with regard to conflicts of interest and compensation of financial planners isn’t the result of self-generated rules and self-accepted regulation, but of “someone ruining it for everyone else”. Put more bluntly, it’s the lawsuits that tend to move the needle more than the lobbyists. Scrutiny by regulators after public exposes on things like the Canadian sales scandal can only help draw attention where it’s needed. Herein, we look toward our anti-trust real estate commissions case.

And Differentiation, or “It’s Only 6%”

The customary 6% real estate commission has been around longer than I’ve been alive. No kidding. The customary deal has been that the seller pays their agent, and in turn, the selling agent pays the buyer’s agent for bringing a buyer to the table. Fundamentally, this means that the buyer pays for everything because they’re the ones borrowing money or writing the check for the total cost of the transaction, but this has been considered a low friction arrangement that provides a healthy income for Realtors and good service for their clients. Or so we thought, until a federal jury found that the National Association of Realtors and its members had effectively conspired to fix real estate commissions for the past several decades. That which we all saw as customary, was perhaps better orchestrated than we thought.

However, as any fair-minded person can point out, this was a voluntary arrangement by everyone involved. You don’t have to work with a Realtor as a buyer or a seller. In Colorado, you are not compelled to engage any professionals whatsoever in the purchase or sale of real estate. Yet, most of us recognize that there’s enough value in the advice and assistance of someone whose full time job is helping people buy and sell their homes, negotiating and navigating the issues with counterparties, and ultimately often resulting in better sales prices for sellers in competitive markets and helping buyers win bids in the same environments. That there was almost always a customary commission around 6% that was then split between buying and selling parties was typically understood by all; in fact, in Colorado, it’s even stated up front in the DORA-provided selling contract how much the buyer’s agent will be paid; a changeable and negotiable number, but still a mandated consideration of the contract.

Suffice to say, in the wake of the anti-trust case, which just settled for $418 million, there will be a shakeup to the real estate commission tradition. Many in the real estate profession are quite concerned about it, and who can blame them? It’s the biggest change since the advent of the collateralized mortgage obligation, which laid the groundwork for mortgages to become cheaper and more easily accessible for consumers, albeit also laying the groundwork for the 2008 crash. Yet, I’m here to say to both consumers and their agents: this is a good change for everyone.

Now, before anyone gets upset, I’m not saying that it’s good that agents might be paid less. Some economists are predicting that real estate commissions might decline as a whole by up to 30% over the coming years, and that will sadly come out of the real estate agent’s pocket. But, I’m saying it’s a good thing that there is now an opportunity to differentiate. Any consumer who has talked to an agent, and any agent who has been to a networking event, will know what I mean by this. Differentiating as a real estate agent is challenging because there is a public perception that all agents do the same thing and all agents get paid the same amount. Yet, in an environment where rates are no longer “fixed” (or at least less fixed than they were before), there is now an opportunity for agents and their brokerages to redefine how they want to differentiate themselves.

Look to the passive index fund we discussed before and the securities brokerages around the same time. In the same year as the advent of the index fund (1975), the New York Stock Exchange got rid of a 183 year old tradition of fixed commissions and let brokers begin to negotiate their own commission rates. The result from both of these events was a rapid acceleration of consumers toward working with more price competitive providers, leading to the rise of Fidelity and Charles Schwab as major “discount brokers” and eventually to being some of the biggest custodians of assets in the world. Because the fact of the matter is, that as technology has expanded and grown, the commodifiable elements of investing have become just that: commodities. Thus, trading commissions are all but gone, and the passive investment product revolution has forced the price of investment products down enormously.

Consequently, while regulation has been slow to force positive changes for consumers and professionals, disruptive innovations like the index fund and removing the fixing of commissions have largely been good for both the professionals and the consumers. Consumers have benefitted not only through directly reduced costs, but also through the invention of differentiation. Consumers of financial planning and advice services must look to qualities other than the offering of specific investment products. Financial planners must specialize and offer key services to a particular portion of the public to stand out. They do so by either being top tier and high dollar specialists, or by offering high volume discounted services. Realtors will now find themselves having a stronger opportunity to do the same.

Ultimately, disruption can take many forms. Where institutional stagnation prevails, unethical sales practices and harm to the consumer thrives (as shown by the less-than-a-week-old expose of the Canadian banks). Yet, financial planners and highly qualified financial professionals have never done better in the United States, and even the less-common example of the fee-for-service or fee-only advisor in Canada has more business and attention than they know what to do with. Realtors in the United States now face a challenging question about whether they’ll attract more business by competing on cost at volume or whether they’ll differentiate and earn more money by being specialized and white glove specialists for a select clientele. Regardless of the route each individual brokerage and agent chooses to take, the consumer will benefit, and ultimately, the top-tier professionals in the real estate profession will as well.

The Pitch

Well the yarn is spun, and I genuinely think that long term, all of this disruption and change will be good for both consumers and the professionals. Still, I would be remiss as a financial planner to at least not offer out the helping hand that we can. If you’re the type who is now worried that their advisor at their bank or credit union might not be acting in their best interest, give us a call or schedule an appointment. If you’re a real estate agent worried for their future, or a real estate brokerage thinking about how they’re going to differentiate given the changes to the professional landscape, our doors are open.

Comments 2

Excellent insight. As always, thanks Dan

How nice it is to have you “up our sleeve” when monetary decisions present themselves.

P