If you hadn’t noticed over the past decade, interest rates have been low. Really low. Historically low, in fact. This has been an enormous economic boon for small businesses, home buyers, and other borrowers of just about any sort. While the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy is to keep the reserve rate low, competition for low rates on every form of loan and credit is fierce. However, with all good news comes the bad: Interest rates are not perfectly correlated with inflation. This means that while rates are low and have stayed low, inflation has begun to creep up (as we mentioned in our piece “Inflation and You” a few weeks ago). As such, a silent threat to the value of cash has begun to emerge. This week, we’re going to review the safest options for keeping capital’s value preserved, and with any luck, we can help you keep your savings safe.

The Cost of Cash

It’s important to illustrate the threat before we identify ways to keep our money safe. Simple thought exercise: If you buried $10,000 in the ground for ten years, how much would be there when you dug it up? The answer? $10,000 and yet it would be worth less. This paradox is powered by the encroaching cost of inflation. If you’d buried those $10,000 in 2011 and dug it up today, while there would still be $10,000 in your hands, it would only have the purchasing power of $8,412.55 by comparison to the time you buried it. In a hyperinflation environment like the 1970s, the purchasing power would have been reduced to $4,464.28. So it’s clear: Sitting on cash, whether buried in your backyard or neglected in your checking account, is a bad play. You have to have some on hand for bills, cost of living, and quality of life, but an excessive amount can be dangerous.

The Safe Harbors of Savings

Most people’s immediate inclination for extra cash is to place it in their savings account. However, it’s important to realize that the national average savings rate in the United States is only .04% APR, which means for every $1,000 saved, you’d make a whopping forty cents per year (or possibly a penny or two more with compounding). Compare this to the depletion of that same $1,000 because of inflation in the past year (2020-2021) alone, while you’d have $1,000.40 in your account, it would only have $971.26 in purchasing power compared to its power of $1,000 a year prior. Even improved by getting into a high yield savings account with a national average for high yield of .5%, you’d have $1,005 and only $975.72 in purchasing power. Much like cash in your back yard or in your checking account, while a higher-yield savings account can help mitigate inflation, there isn’t a savings account option combating inflation well enough to completely offset it.

The Safe Harbors of CDs and Money Market Accounts

At present, the next step a banker might suggest would be a Certificate of Deposit (“CD”) or a Money Market Account. Much like the savings account, however, there lies a potential trap. The national average for a CD at the present time is 0.17% for a 1-year lockup and 0.31% for a 5-year lock-up. This means that cash invested in a CD at the national average rate would yield less than a high yield savings account! To boot, a CD carries a significant interest rate and reinvestment risk. Simply put, if rates went up at any point after you opened the CD, you’d run the risk that you could be getting a better rate of return if you had your money invested in an accessible manner. Even on the strong side of CDs, rates for higher yield institutions are capping out currently around 0.55% for a 1-year CD and 0.8% for a 5-year CD, which of course still doesn’t beat out our current rates of inflation or mitigate the risks already highlighted. An alternative might be a Money Market account, but similar rates to the 1 year CD are prevalent and these ultimately will not largely preserve the value of your cash. One important note as well is the distinction between a money market account and a money market fund. A money market account has an FDIC-insured guaranteed rate, while a money market fund is just an ultra-conservative investment vehicle attempting to match or beat inflation at a low level of risk.

The Safe Harbors of Treasuries and I-Bonds

Despite the standing risk of inflation, there are some safer places. One option that has recently made the news is the I Bonds issued directly by the US Treasury. These bonds pay a fixed rate on top of the current inflation rate, meaning that they adjust their yields to the current inflation environment, effectively ensuring a return on the investment that is higher than inflation. For example, at the current moment (6/8/2021), the yield is 3.54%, meaning that $10,000 invested today would come out at the end of the year with a value of $10,354, and a net of inflation purchasing power of $10,052. However, there are some limitations to this strategy: I Bonds can only be purchased directly from the US Treasury and are limited to $10,000 of purchases per calendar year. Additionally, there are some lockups: You cannot redeem the I Bonds for one year, and if they are redeemed within five years of purchase, the previous 3 months of interest is surrendered. This means that they aren’t appropriate as an entirely liquid holding, but they do stand up better than conventional banking options so long as the investment need isn’t too significant.

Less-than-Safe Harbors

Ultimately then, with little purchasing power protection on the horizon, we then have to look at savings instruments that aren’t guaranteed, and thus we lose the idea of a “safe harbor” where the outcome is assured and insured by the government, FDIC, and NCUA insurance. Herein our analysis will be concise: An ultra-conservative investment portfolio can be a significant aid in helping to preserve the overall value of your assets. However, it is not an assured course and should be avoided when the intended holding period is less than several years since there is a short-term risk that volatility could reduce the value of the initial investment and make it unusable without accepting losses for months or years.

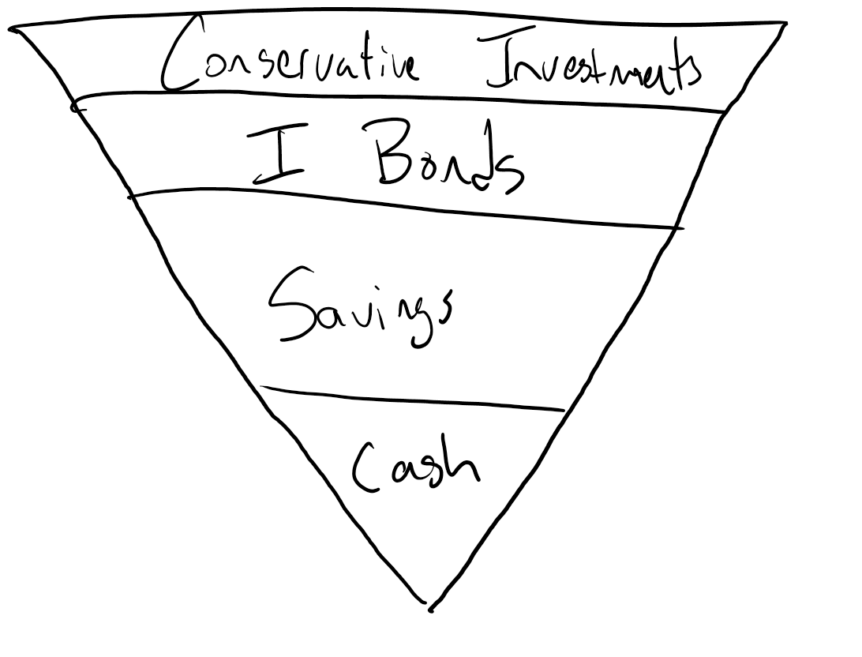

A Safe Harbor Formula

Let’s get down to brass tacks: How do you protect your money? Well, for this we recommend an inverted pyramid approach, where the smallest amount and no-return cash are at the bottom, and larger and higher return assets are at the top. First, we recommend keeping approximately one and a half months of your typical expenses in checking. This allows for a consistent ebb and flows for your day-to-day expenses and you can regularly replenish this position with each paycheck. Next, we recommend keeping another two months in your savings account. While the checking may yield nothing or next to nothing and the savings account will not beat inflation, we want to ensure you have at least a few months of savings immediately available to you in the event of an emergency like a high deductible insurance bill, or in the event, your income is interrupted. Past the point of that three and a half month buffer, we can start to look for higher yield safety. Our first stop would be the I Bonds, as they’re going to immediately help with the ratio of your savings. Assuming you don’t need to save more than $10,000, this might provide the only extra shelter you need. If your savings and reserve needs are greater, past this point we’d suggest investing an additional $10,000 into the I Bonds annually to provide a safer harbor. Note that we’re functionally not recommending CDs or Money Market accounts. Even at high yield institutions right now, with historically low rates being kept down by the pandemic, we’d view the reinvestment risk and interest rate risk as too great for any investments that have a lockup period without an inflation adjustment. Past the 3.5 months of checking/savings plus $10,000/year of I Bonds, we would recommend an ultra-conservative investment portfolio for your emergency savings. At some point, you may build up a large enough reserve to turn to invest more aggressively, but in total, the combination of checking, savings, I Bonds, and your conservative portfolio should equate to six months of expenses. Past that point, you can afford longer-term and more high-yield high volatility investments, assuming you don’t have a large expense coming up that you’ll need the money for!

Dr. Daniel M. Yerger is the President of MY Wealth Planners®, a fee-only financial planning firm serving Longmont, CO’s accomplished professionals.

Comments 1

This is great! You have pinned down exact numbers that have been only vaguely in my mind. Good, objective thinking here that is useful. Thanks