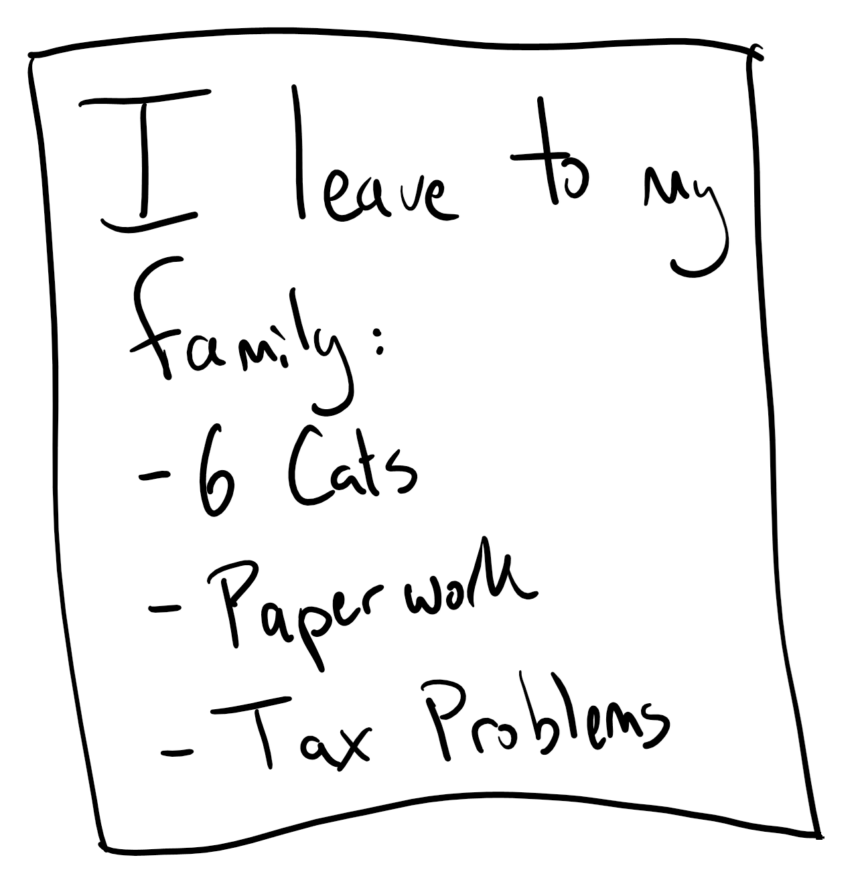

As the old saying goes, the only two certain things in life are death and taxes. Today, we’re talking about both. Inevitably, through no fault of your own, you will pass away. Turns out there is a 100% chance that you will not live forever! Sadly, you and everyone else share this fate, and consequently, you also share the obligation to prepare for what you may leave behind. While it’s the subject of an entire field of law (Estate Law) to advise you as to how to establish trusts or legal documents such as wills, it’s a less glamorous subject that many of your assets may pass by mechanisms that involve tiny bits of paperwork through your working and retired life. So today, we’re talking about what happens to your financial accounts and assets when you pass away, and how what you do with them while you’re still with us, affects your heirs.

Inheriting a Non-Retirement Account

Let’s start with the basics: a non-retirement account. This could include your checking and savings accounts, CDs, money markets, or a non-retirement brokerage account held at an institution like Charles Schwab or Fidelity. Assuming you own the account(s) in question individually, there are a couple of things that will occur upon your passing.

First, if what you held were investments with a cost basis (e.g., you bought a stock for $20 and now it’s worth $100), then your investment’s cost basis will jump up to its value as of the date of your death. Good news, this means your heirs might save quite a bit of money in taxes! This also means that your heirs will receive their inheritance in kind. However, the way this happens can differ.

If you’ve established “Pay on Death” or “Transfer on Death” (“POD” or “TOD”) instructions with your financial institution, your beneficiary will be entitled to receive the balance of the account “by process of law,” meaning that the account bypasses probate or estate administration, pending any claims against the estate that might be made by secured creditors. Essentially, this means that you’ll fill out a new application with the current custodian of the assets (i.e., Vanguard, Charles Schwab, Fidelity, the bank, etc.), and they will transfer the balance of the original owner’s account into your account, or your assigned portion if there was more than one beneficiary.

If the account did not have POD or TOD instructions on file, it will either pass through probate or if the original owner established a trust that “pulls assets in” upon their death, it may first go to the trust for administration and distribution by the trustee based on the trust’s instructions.

Inheriting a Retirement Account

(Including: Traditional IRA, IRA Rollover, SEP IRA, SIMPLE IRA, 401(k), 403(b), 457(b), and Defined Benefit/Pension Plans.)

Here, things get a bit more tricky. Most particularly, the most important thing is your relationship with the person who has passed away or your beneficiary’s relationship with you. There are a couple of basic examples of inheritors to consider here:

Spouse

If you are the spouse of the person who has passed away, you have a couple of options available to you. First, you can simply combine your departed partner’s account into yours and essentially be done with it. For example, you both had $100,000 in separate IRAs, and afterward, you simply have one IRA with $200,000. However, a couple of other options present themselves here: You can choose to maintain the IRA in an Inherited IRA account, and if your spouse was younger than you, you can use their date of birth as the basis for required minimum distributions. This means you can avoid paying out higher amounts of pre-tax income from traditional IRAs later on in life, which is valuable if you were older than your departed spouse. There is also another set of options for spouses we’ll discuss in a moment under the non-spouse rules.

Non-Spouse

Here, there are two types of inheritors: “Eligible designated beneficiaries” or “EDBs”, and everyone else. To be an eligible designated beneficiary, you must have been the spouse, or you are not more than 10 years younger than the original owner, or you are chronically ill or disabled based on IRS guidelines, or you are a minor child of the original owner. If you are an EDB, you are given the option to withdraw the balance over a lifetime based on the required minimum distribution rules, meaning that you might be able to drip and drab out distributions over decades, potentially reducing the tax impact of distributions.

If you are an EDB or you are not an EDB, then you have essentially a single rule: distribute the balance within 10 years. You can do this in bits or chunks over the course of ten years, but it must be done by the end of the 10th year following the death of the deceased. So, someone died on January 1st, 2024? The balance must be taken out by December 31st, 2034. This ten-year timeline means you can break up the distribution for tax purposes or to better control and time your cash flow, but it does mean that it must be done sooner rather than later, in consideration of your own life expectancy.

Entity

In the event a retirement account has been left behind to an organization or trust, the beneficiary entity has up to five years to withdraw the balance of the trust. They can do this as a lump sum or in chunks over the five-year period, but like the ten-year rule for individual beneficiaries who aren’t EDBs, all money must exit by the end of the fifth year anniversary of the passing of the individual. One noteworthy exemption here is that some trusts are structured as pass-through trusts for beneficiaries; in these cases, the ten-year rule can apply to the beneficiaries of the trust rather than the five-year rule applying to the trust itself. However, this requires that the trust language specify these intentions and provisions in advance, not retroactively.

What About Taxes?

There are a couple of tax considerations in inheriting an account or accounts and assets. In the case of inheriting a non-retirement account, it’s unlikely that you’ll have a tax problem here unless the total estate exceeds the estate tax exemption, which is currently over ten million dollars per individual, though this is going to drop with the expiration of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act at the end of 2025, after which it will revert to a measly few million per individual. Also, note that some states do have their own estate tax exemption and tax rates, so keep that in mind. However, assuming the estate is below the estate tax exemption, any non-retirement assets will essentially be inherited tax-free upon receipt, and then there may be taxes later on based on changes in value, interest, or dividends received after the date of death.

In the case of the retirement accounts, inheriting a retirement account means that you inherit the special tax treatment of the account. For pre-tax accounts such as traditional IRAs or pre-tax 401(k) plans or pensions, you will have to distribute any RMDs that were due the year of the death, and any distributions taken subsequently, whether as a spouse, within the 10-year rule, or the 5-year rule, will be subject to income tax on a state and federal basis, though these distributions don’t trigger payroll taxes such as social security and medicare. In turn, the inheritance of Roth assets is tax-free, so there is a material benefit to holding onto the Roth assets until the very last moment before distributing them, since the entire distribution will be tax-free.

Inheriting an Annuity

There is a special treatment for annuities that are inherited. In the case of the retirement account owning annuities, the tax rules described above apply. However, in the case of a non-retirement annuity, any distribution of value above the cost basis of the annuity is taxed as income, rather than subject to capital gains. Because annuities enjoy special tax deferral benefits in non-retirement accounts during the lifetime of the owners, the returns generated by them are taxed as income and at income tax rates, rather than enjoying preferable capital gains tax rates.

Comments 3

I suppose it is too late to change my traditional IRA to a ROTH (tax free!) IRA since I have long since retired – Where were you 20 years ago when we retired?

P

Author

We can always discuss post-retirement conversions!

You made a complex topic simple. Thanks Dan!