An Author’s Note at the Outset: About a dozen agents lacking in reading comprehension have rushed forward, shrieking their objections to this post without actually reading it carefully. So, I’ll put the warning up front: the purpose of this post is to highlight that a traditionally structured product is not a strong wealth accumulator. It is not to demonstrate a max funded policy; that is not it’s intent, was not it’s intent, and it is not structured in any way to resemble a LIRP or other life-insurance-as-an-investment policy. You can cease frothing at the mouths now and try to engage your cognitive faculties.

Onto the original post…

If you’ve spent much time on the internet, particularly Tiktok and other “hip” social media channels, you will find that much of the internet is flooded with advertisements for things like “Bank On Yourself,” “Infinite Banking,” and “Maximum Premium Indexing” or “MPI Strategies.” The people advertising these strategies make it sound like they have indeed, invented something greater than the wheel or sliced bread. Yet, the larger financial planner community rolls their eyes and mocks these supposed charlatans for their misleading advertising and marketing. So what’s the deal? Well the truth is that all of these strategies rely on selling consumers a permanent life insurance policy, either in the form of a Whole Life or Universal Life policy, depending on the exact nature of the strategy.

Are these strategies game-changers? No, not at all. Yet with some of these salespeople wielding million-plus followings on social media and spending their time acting like influencers rather than financial professionals, they gain a disproportionate amount of attention, and thus, hundreds if not thousands of people are being sucked into buying incredibly complex products every day. Yet, it might surprise you to know that despite how I’m talking about them, I actually own a Universal Life Policy. Specifically, a “Minnesota Life Accumulator VUL” from Securian Financial. Today, I’m going to explain how and why I sold the policy to myself back when I was a fee-based advisor, what it looked like when I constructed it for myself, and how it looks today.

The Illustration

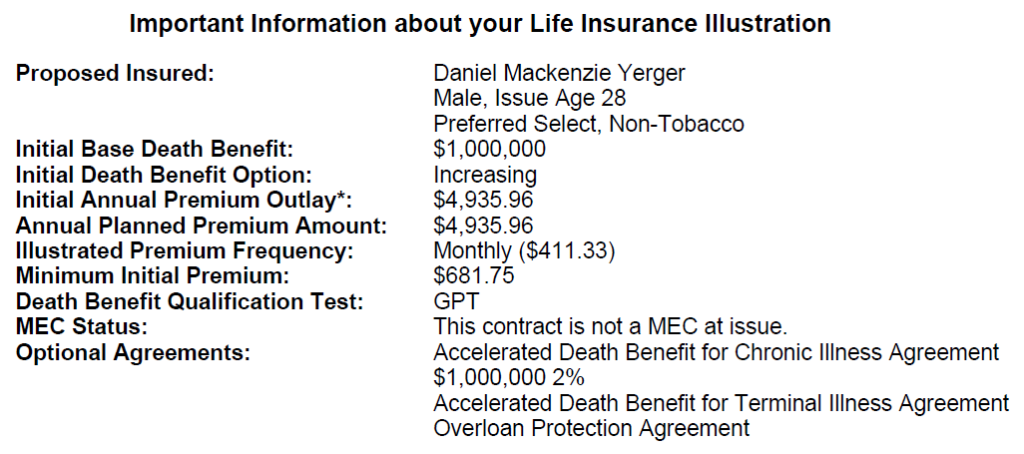

A full copy of the illustration is available here (Yerger, Daniel – Accumulator VUL). I started writing the policy on 10/26/2018 and the policy was issued on 12/1/2018. Here is the summary description of the policy’s features and how it was applied for:

As shown, the policy had $1,000,000 in death benefit coverage, and was classified as “increasing.” This means that as the cash value in the policy grows (money that is mine, not the insurance company’s), the insurance company will always be at risk that it must pay out $1,000,000 on top of the cash value in the policy. Most policies have a level death benefit, in those cases, the insurance company’s risk is the greatest as of the date they issue the policy and declines as you keep paying premiums into the policy, shrinking the difference between the cash value and the death benefit. The other major feature that I went out of my way to apply for was the Accelerated Death Benefit for Chronic Illness Agreement. Long term care needs are common in my family, with two great-grandparents who lived to be over ninety years old, and a grandmother currently suffering from Alzheimers. Funding my potential long-term care needs early in life, along with creating lifelong insurance protection for my future family, were my key intentions.

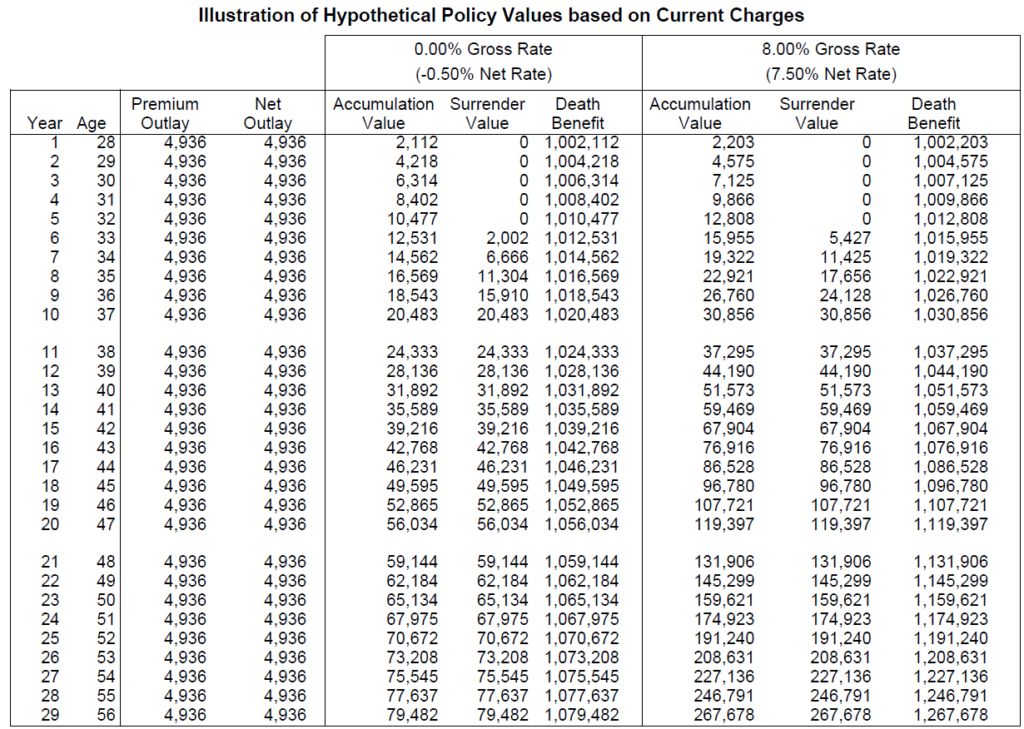

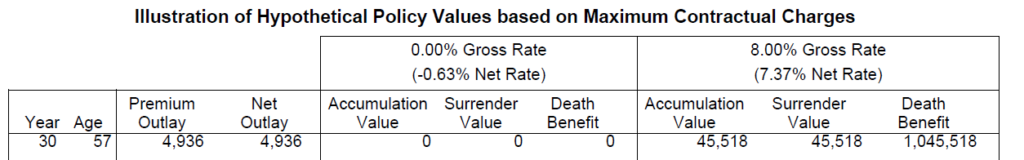

This is the first half of the illustration’s table showing expectations for the policy over its first 30 years. Today, we’re in the 5th policy year (completing 4 years), so the expected value of the policy is that, if the investments in the policy performed as expected (8% gross, 7.5% net after subaccount fees) that I would have $12,808 in the policy and $0 of net value after surrender fees were subtracted. After 4 years of paying expected premiums of $4,935.96 a year ($19,743.84 total), I would have a death benefit of $1,012,808, and $0 in liquid cash value available to me. In other words, I’d have paid a lot for life insurance, and would have a 100% negative investment return on my investment so far (unless of course, I died.)

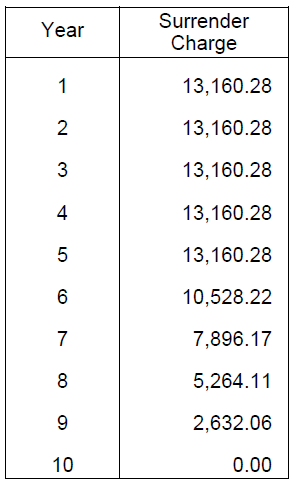

It’s also noteworthy that because of the surrender charges on the policy, I’m not expected to have full access to the cash value of my policy until its 10th policy year. From year one through year five, the surrender charge is expected to be greater than the cash balance, and from years six to nine, the surrender charge shrinks enough that the cash value finally “comes out” and is accessible.

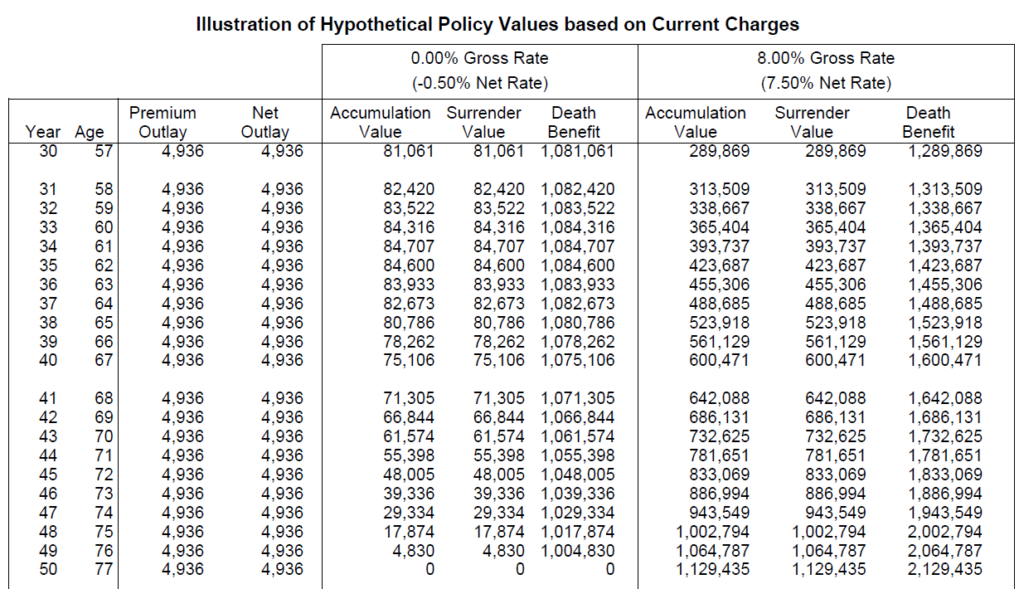

Here is the second page of the illustration table, and it highlights a critical thing. The policy has no guaranteed returns as a variable policy. While the probability is excellent that I’ll show a decent rate of return over a 50-year period, the illustration points out that the cost of insurance will have grown so significantly that if the policy yields a 0% gross rate of return and thus a -0.5% rate of return after fund expenses and policy expenses, that the policy will lapse when I turn 77 in the 50th anniversary year of the policy. Alternatively, if the rate of return on the policy has managed it’s 8% gross, the policy will have $1,064,787 in cash value and a death benefit of $2,067,787. A variable policy is the riskiest form of permanent insurance, because I carry all of the risk of the investment returns of the policy, the insurance carrier only carries the risk of the million-dollar difference between the cash value and the death benefit.

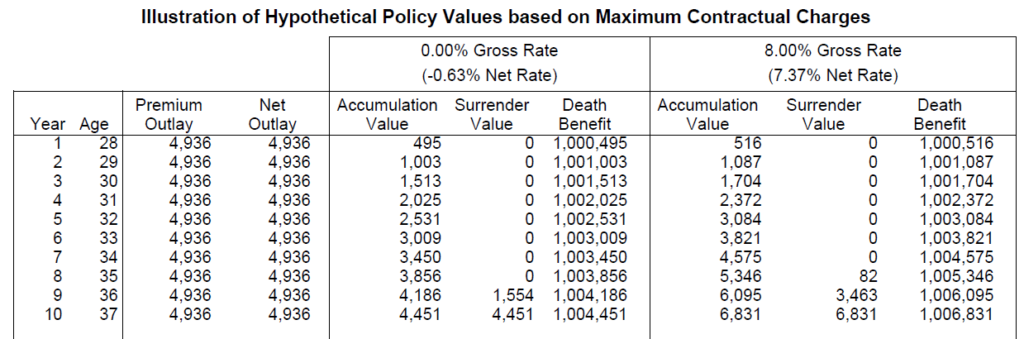

Of course, the illustrations we’ve looked at so far assume charges and costs remain “level” or “normalized.” Insurance policies have the ability to increase costs if mortality rates and expenses are greater than anticipated by the actuaries at the insurance company. Thus, we can see that if expenses are as high as they can be, I’m not expected to see cash value until year 8 (see above), and based on the highest expenses and a 0% return on the invested cash in the policy, the policy could lapse as early as age 30 (see below.)

Surrender Charges

A critical component of any life insurance policy is the surrender charge. Simply put, the Surrender charge provides a minimum buffer for an insurance company to do two things: 1) Recoup the cost of the commission paid to the agent who sold the policy (typically 80%-120% of the first year’s premium) and, 2) Cover their disproportionate risk at the date of issue in the policy. This is a critical thing to be aware of, as many investors in permanent life insurance policies being sold the “living benefits” of life insurance for bank-on-yourself or MPI strategies are often told that the financial benefits of the policy will be immediate and that there will be a significant return on their investment. Yet, even if a policy is “overfunded” to the maximum permissible limit, on day one, any buyer of a life insurance policy is looking at an immediate negative return on their investment due to the costs of insurance and the surrender charge they will face if they take money out of their policy. Most surrender periods are between five and ten years, though I’ve seen some stretch out as far as twenty years. The longer the surrender, typically the lower the costs of the policy (less risk to the insurance company), and the shorter the surrender, the higher the costs of the policy.

How the Policy has Actually Performed

A copy of the most recent annual summary report of the policy is here (Yerger, Daniel – Securian VUL Policy Review – 1-4-2023). Let’s talk about the major highlights of its performance so far.

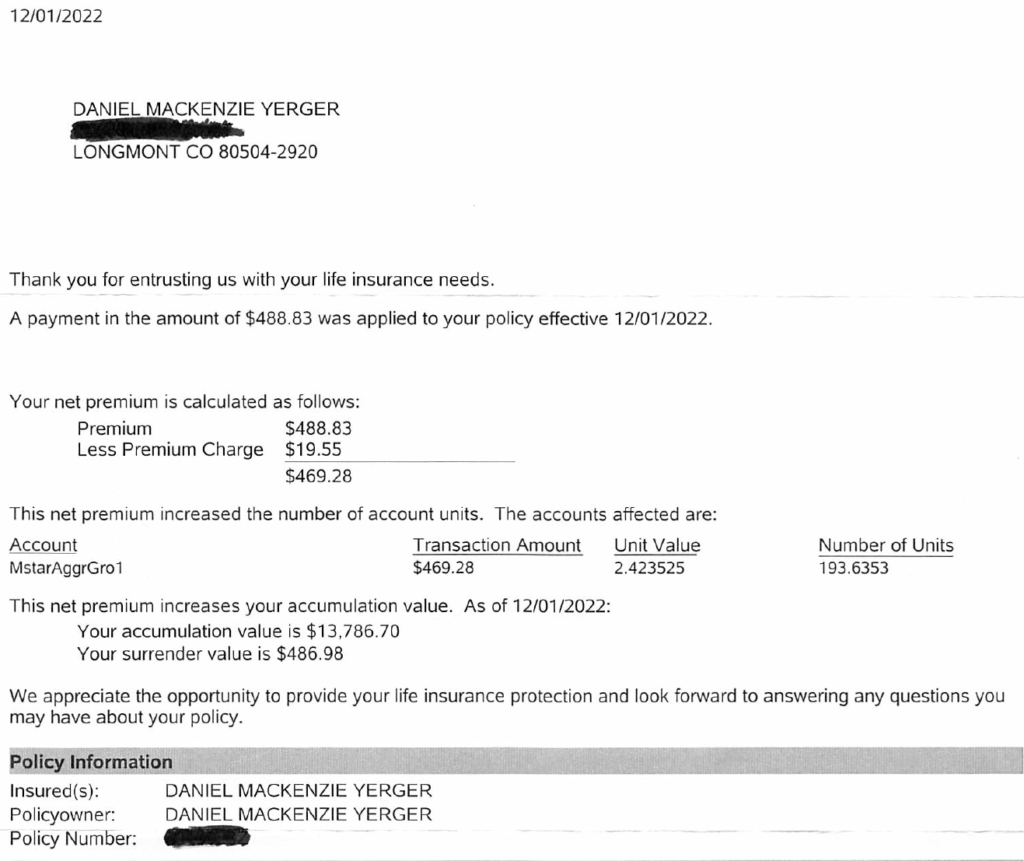

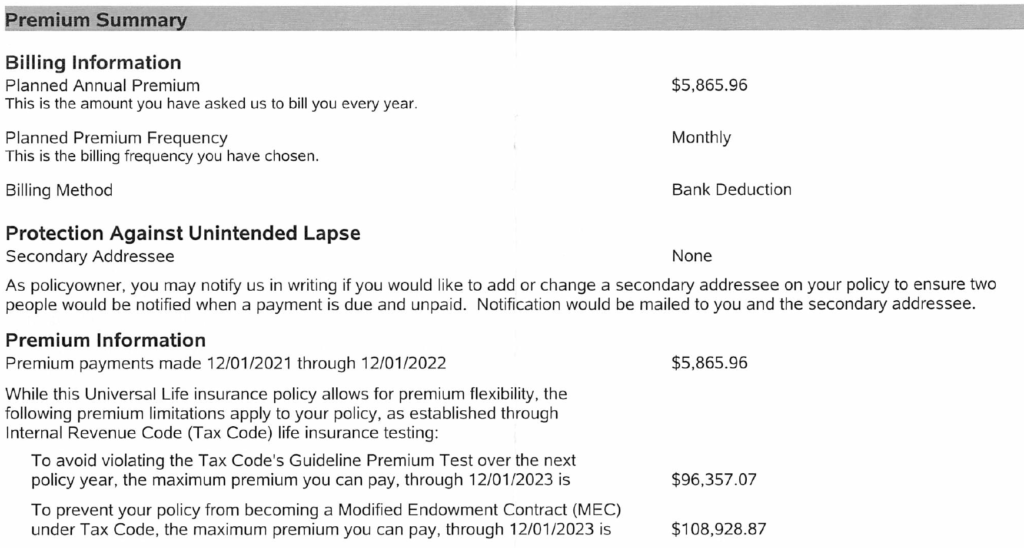

This first image shows a copy of the monthly statement I receive when my premiums are paid. Because underwriting did not rate me as highly as applied for, my annual premiums ended up being $5,865.96 rather than $4,935.96. This means the policy has, as of this statement, cost $23,463.84. You can see that the balance of the policy is $13,786.70, but because of the surrender charges, if I were to try to take my money out of the policy today, I’d only walk away with $486.98, or a -97.91% rate of return on my premiums (plus whatever you value four years of life insurance coverage in which I didn’t die.)

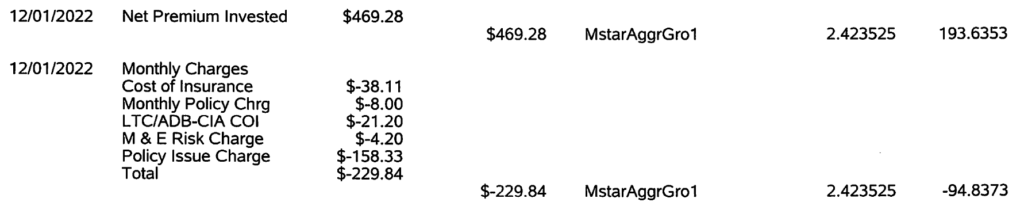

A little further in, we can see the transaction report for my policy month by month. For that same premium payment receipt we just saw above, we can see the underlying expenses of the policy. Of the $488.83 paid, $19.55 was immediately taken off for the “premium charge.” Of the remaining $469.28, $38.11 was spent on the cost of insurance (the $1 million policy coverage that the insurance carrier is at risk for), $8 was a monthly policy charge (an extra cost for paying monthly instead of annually), $21.20 was for the Chronic Illness Rider (Long Term Care Insurance), $4.20 was for the “mortality and expense risk charge,” essentially an administrative fee on top of the cost of insurance, and $158.33 was for the policy issue charge, which should eventually fall off after the commission for selling the policy is recouped. All of this totals out to only $239.44 of my $488.83 being invested in the policy. In other words, my immediate purchase of insurance makes the investment return of my policy -51.01% right out of the gate. Not very good for an investment expected to yield a net 7.5% return annually. If that number holds true, for every premium payment it will take 6.8 years just to break even on the premium payment before I see any positive return on investment net of the costs of the policy.

An option available to me, and touted by those agents selling policies, is the ability to take out a lower death benefit policy and then to overfund the policy as much as possible. That certainly can reduce the cost of the insurance net of the premiums paid. If I were to fund my policy to the maximum extent permitted under the guideline premium test, then the expenses would shrink to 2.98% of the premiums paid into the policy. Essentially, this would be equivalent to purchasing a middle-of-the-breakpoints Class A Share Mutual fund (with sales charges ranging 5.75% to 0% depending on your investment of $1 to $1 million dollars). Yet, if I’m looking for a strong return on my investment dollars, I could invest in a Vanguard ETF for as little as 0.02% per year, not have surrender charges or costs of insurance, and go about my day.

Tax-Free Income?

Of course, the last benefit insurance salespeople tout is that of the “tax free income” these supposed strategies can provide. They point to a couple of features of permanent life insurance to make this misleading claim:

- The cash value in a life insurance policy does not trigger income taxes as it accumulates.

- The death benefit of a life insurance policy is tax free (so long as it’s below the estate tax exemption on conjunction with the value of all of the assets the decedent owns)

- Loans taken from the policy are not subject to income tax.

That last one is a big deal, because it’s the key to the whole charade. If you surrender a life insurance policy or distribute cash value to yourself, the amount of cash value net of the portion of premiums paid that funded the cash value (note, not the gross amount paid to the insurance company) is treated as taxable income. Not a capital gain (0%, 15%, or 20%), but taxable income (10%-37% federal plus state income taxes.) This is substantially worse tax treatment than that of a brokerage account selling investments at long term capital gains rates.

The way that agents get around this is by selling policies with loan options available. By taking a loan out against the policy, they claim that the cash value will continue to grow at a rate greater than the loan interest (which they can’t actually guarantee), and that the amount loaned to you is not subject to income tax. That is true, but let’s ask the question: Do you treat your mortgage as tax free income? What about spending money on your credit cards, is that tax free income? If you take out student loans, is the balance of the loan tax free income? Of course not. By taking a loan out against the policy, the insured is locking themselves into continuing to pay premiums if necessary, along with having to repay the loan and interest. If they fail to repay the loan or die while the loan is out, then the balance of the loan is converted into taxable income, and the tax advantages of the policy evaporate.

In Conclusion

Life insurance is great at what its name implies: Insuring the life value of a person. It is great for protecting your spouse, children, and others from the loss of your life and the income and financial value it can produce. There are many advanced and unique strategies for using life insurance in an investment, compensation, or retirement plan. Yet, there is no version of life insurance that functions better as a savings and investment vehicle than the vehicles actually designed for that purpose: stocks, bonds, real estate, mutual funds, exchange traded funds, and even low-cost variable annuities (rare, but emphasis on low-cost on that last one.) None of these options carry the burden of surrender charges, the costs of insurance, or the other headaches that come with life insurance policies when they are used for a purpose other than insuring a life. The same tax advantages touted by insurance salesmen exist in annuities. The strong investment returns claimed from these policies can be achieved at lower costs in normal investment products. The simple fact of the matter is that while utilizing life insurance policies “to the extreme” can yield positive financial results, there is little additional value created in adding additional costs to an investment strategy.

So, at the end of the day, most people should be buying a term life policy for their needs. Maybe one in twenty needs a permanent policy for some specific reason (I gave the reasons for my own), but otherwise, we should keep our finances as simple as we can and keep our costs reasonably low as we pursue our desired financial outcomes.

A final admin note: I’m sure some insurance junkie (no offense, agents and brokers) will comment here or elsewhere to say that “I just don’t understand these strategies.” Far from it, I was eligible for the Million Dollar Round table several times during my stint as a fee-based advisor; I went on due diligence trips to multiple insurance carriers and met with about every insurance wholesaler out there. I have discussed these strategies at length, looked at the illustrations and the hypotheticals, and so on. I have never once seen an example of a “wealth maximizing life insurance policy” that netted out better than the results of a diversified portfolio. I have had agents tell me they can show me one in the past, but upon examination, they have never passed muster. Feel free to take a swing at it if you like, agents & brokers, I’m open to seeing a Unicorn for once.

Comments 4

I agree with your analysis. Life Insurance was important when we had a mortgage but after that our savings served as our insurance. There is risk, of course, especially if we dwindle into our dotage and need special care for years. I choose to bet on my genetics that are long lived and mentally, physically healthy. It’s a risk but I subscribe to playing the odds. Since winning the lottery is probably a million to one, I don’t play. Same with life insurance. I am counting on my savings to see me through – ummmmm, that’s where you come in, LOL.

Daniel, You expected this apparently, so here goes. I am sorry to inform you, but it looks like you did this all wrong. If you were just looking for death benefit with a meager cash value build up, then you accomplished that. If you were looking to build cash then you did it all wrong. The policy illustration from the git go is not a max funded policy. My definition of how a max funded policy structured is essentially where you buy the least amount of insurance for the most amount of money. Not a $1,000,000 death benefit for a paltry $5k a year. The plan for a max funded policy is a policy is purchase the lowest Non-MEC death benefit for the money. Today, for a male 28 at the best insurance rate, that would be about $100K or a bit less depending on which company you chose. Also, the policy performed as illustrated, actually better, as the illustration shows no cash available for surrender until year 6 but here you are, with about $500 in year 4, if you cashed it in. So the policy you bought based on this illustration has more cash than illustrated and you seem to think it’s a bad deal. I understand that you sold a lot of insurance in the past but if all of the policies were structured like this one, when the goal was maximizing income, then you need to go back to your clients and try to fix those policies.

Author

Thank you for your thoughts, Louis. You seem to have missed the point entirely, but that’s alright. Nothing you stated is incorrect insofar as comparing my death benefit & LTC-oriented policy to a policy constructed for max funding. That said, I never claimed that max funding was the purpose of the policy. The point, which in your rush to upset you have missed, is that a traditionally structured policy is not the “wealth building secret” that many agents sell it as. An accumulation-oriented policy can be a mediocre if growing investment, but life insurance for its stayed purpose is not a strong investment. Do take care to read a bit more carefully in future.

Pingback: That Doesn't Look Like Anything to Me