Speculation is in vogue right now and it’s the dearth of realistic thinking that drives it. Whether it be calls to invest in dog-based cryptocurrencies or special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs) being used to dodge SEC disclosure requirements for initial public stock offerings, you can’t take a single step in the financial world without bumping into someone who is excited to inform you that they’ve put their life savings into something on no material basis other than their excitement about the thing. It goes even further to the land of ludicrous that there are now companies popping up claiming to offer research on these speculative offerings: offerings that contain no intrinsic or material value, generate no product, profit or loss, or any other material sign of management or leadership in their space. Based purely on technical analysis and chart tracking, this “research” is as useful in predicting the movements of cryptocurrencies as yesterday’s edition of the wall street journal can help you predict the movement in the price of dog food today. As the joke goes, “technical analysis is astrology for investors.” So today we’re taking a break from all the noise to lay out the challenges of having an investment process rather than engaging in speculation or absentee investing.

The Rules of Fiduciary Investment Management

Without getting too far into the weeds of legal statutes, there are actual rules and duties that a fiduciary asset manager must follow to be qualified as acting in good faith that they are genuinely attempting to manage investments on a fiduciary basis. Decades ago, the basis for this was known as the “prudent man rule,” which essentially boiled down to the idea that a prudent person would have made the investments they made knowing what they did at the time. While simple and “easy” to follow, the rule proved unhelpful in identifying whether an investment was truly made with the best interest of the investment’s beneficiaries in mind. In 1992, the rules were updated under the “Uniform Prudent Investor Act,” which laid out more specific requirements among the existing rules:

- That the entire portfolio must be considered in light of a specific investment’s appropriateness within the portfolio

- That diversification is an explicitly required duty; a prudent fiduciary cannot overconcentrate a portfolio for any reason

- No category or type of investment is intrinsically bad, but the needs of the portfolio’s beneficiaries must be considered when selecting investments

- That speculation and outright risk-taking are not permissible under the rule

- That fiduciaries may delegate to qualified third parties (i.e. use investment funds rather than selecting stocks)

Past Performance is not an Investment Process

One of the most popular things you will read or hear from people enthusiastic about speculation is how much money they’ve made while speculating. While we all applaud someone’s fortunes taking a turn for the better, the problem with this is selection bias. Those who have “speculated and won” are ecstatic and share their story. Those who have lost everything because of their speculation are hardly likely to boast about their choices. Beyond those who are speculating, most investors really don’t know how their portfolio is actually performing. It’s good to know that the numbers keep going up over time, but are they going up at the pace, faster, or slower than the market? Within that question are also things like consistency, cost, and level of risk-taking to accomplish those paces. While it might be exciting to see double-digit returns from a fund in one year, would you be as comfortable knowing that it happened because the fund manager took on enormous risk to do so? What if a fund’s performance drags for months or years? How do you know it’s the fund and not the market more broadly? All of those questions to highlight that most publicly available tools for investment research on performance are entirely historically driven and typically only look at the fund itself; to compare, an investor has to go about pulling up the dozens or hundreds of comparative funds, be fluent in terms like “R2” and “Traynor Ratio,” and have the tools, capacity, and knowledge to make the comparisons. For those truly passionate about the endeavor, there are paid tools and software programs out there, but they do typically cost thousands of dollars per year and the economy of such an investment only makes sense for the ultra-wealthy to use. The underlying “trick” here is that the search for information is expensive. Not only in the cost of software or research tools but also in time. For every hour someone spends trying to find the perfect emerging markets fund, they’re giving up an hour of wages at work, an hour with their kids, or an hour they could enjoy pursuing hobbies. To manage an investment process like the one MY Wealth Planners® delivers to its clients would cost approximately 1,500 hours per year for an individual to accomplish: hardly a fair tradeoff for the return they’re likely to achieve.

What About Keeping It Simple?

As the saying goes, “The greatest trick the devil ever pulled was to convince you he doesn’t exist.” While far from a theological point when it comes to investing, there is an entire cottage industry of bloggers, F.I.R.E. adherents, and financial advisors out there attempting to make the argument that investing is so easy that anyone can do it. You can google a “three-fund portfolio”, read a bogleheads blog, or buy any number of airport bookstore books on investing that will tell you that you really only need one or two funds and the rest will work itself out. The problem here is the snuck premise: “You’re a smart person, so surely you’ll pick exactly what professionals would pick and do just as well, but at a fraction of the cost!” And to some extent, that logic isn’t entirely untrue. Many studies have shown that professional stockpickers and fund managers can’t outperform the basic benchmarks of their fund and that most day traders lose money over the long term. However, none of that simplicity encompasses basic traps a DIY investor can fall into. Do they invest in Fidelity’s no-fee S&P500 fund, only to find out that in using their platform they can’t investor in Vanguard funds without paying a $50 ticket charge every time you invest in the fund, rebalance, or trade out? What about investing through a digital investment service like Ally Bank or Charles Schwab’s intelligent portfolios? After all, they offer to manage your money for free! Of course, they use proprietary funds or funds with revenue sharing agreements and keep anywhere from 10%-30% of the investment in cash and make money on the spread of lending that cash. So while you don’t see a fee, is it actually free?

Perception is not Reality

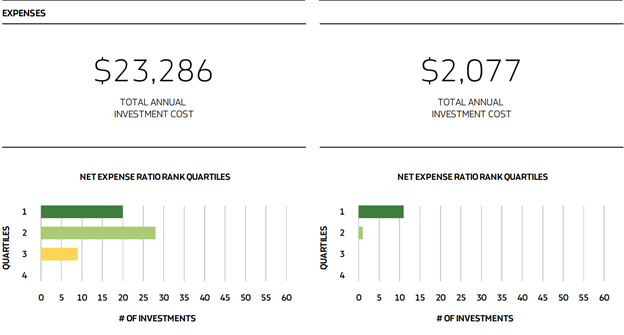

Yes, it’s reality in the spirit of that expression, but not all the time or every time. Let me give you an example. A few months ago we sat with clients and logged into their 401(k) accounts to re-balance and establish the investments for their portfolios. They were, across a four million dollar portfolio, spending over $38,000 in fund expenses, and our proposed mix would cost them only $2,100 per year in fund expenses for the same size of portfolio. As we went through the asset classes, the husband held up a hand: “Wait, you picked the wrong one.” I was confused and asked him why he thought that: “Because you’ve picked the cheapest one every time and you just picked one that’s more expensive than the other.” That was entirely true, but the reason I’d done that was because the “other” he was referring to was a fund that didn’t provide the allocation we were looking for. In our conversation about the reason for making changes to the investment portfolio, he’d come to establish a heuristic (a mental shortcut) that the only thing that mattered was picking the cheapest investment funds. While that was certainly a major part, it wouldn’t have helped to have already picked out a cheap European stock fund only to then buy another European stock fund in lieu of the emerging markets fund we were looking for.

Let’s Look at an Example

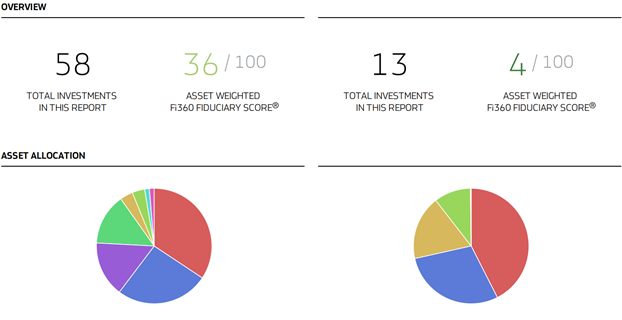

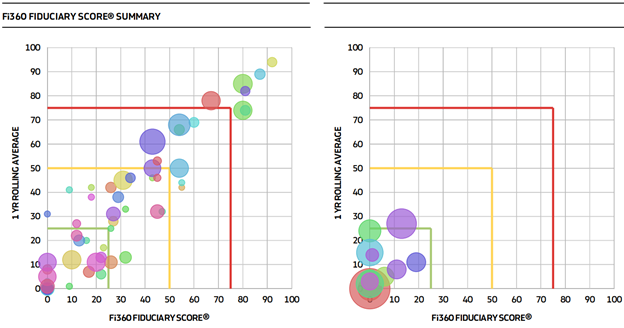

This is a real portfolio comparison for a real person. We’re going to show a comparison between their existing investments (on the left side) and what we’d recommend (on the right side). Having given these people this comparison, they could easily go buy the investments on their own and not think twice. They’d be better for the change, their only risk would be that the investments came out of alignment, started dragging in performance, etc. At stake in that risk? $3.2 million dollars.

What we first see is that this individual has over-diversified (58 funds!) While diversification is great, when making investments over a lifetime, it can be easy to end up with overlapping duplicates and issues. And the problem shows here with the fiduciary score, which simply is best at a score of 0/100 and worst at a score of 100/100. The fiduciary score reflects a large number of metrics, including performance over the past several years, risk levels in the portfolio, returns relative to peers, risk-adjusted returns relative to peers, the tenure of the investment manager, the cost of the funds, and more.

In this chart, we can see the scatter of the individual’s investments. While many are in the ideal top 25% of both performance and fiduciary scoring metrics (the bottom left corner), dozens of the investments are poorly performing both in true performance and when compared against their peers, as shown by the scatter drifting up and to the right.

Finally, this individual was emphatic that their investments were all low-cost index options. While the label of the funds all included “index-like language,” the fact was that more than half of the portfolio was in expensive actively managed funds. And the difference here shows, with a difference in cost between what they had selected over the years and what we’d recommend today, the investor could save $21,209 per year.

So What’s a Good Investment Process?

I could lay it out point by point, but let’s focus on the most important thing within the process: Know your limitations and what your time costs. That’s the serious point of interest. There are millions of investors out there who every day do not know what they’re investing in. That includes both passive investors who were auto-enrolled into the 401(k) plan without making an investment selection and active speculators who are just buying anything they read about on Reddit, hoping that lightning will strike twice. Understand that to access tools that give you adequate information to call research, rather than what pops on google, is an expensive investment in itself. Finally, understand the scope of the economy of scale you’re competing against. If you want to buy individual stocks, you’re competing against hundreds of billion and trillion-dollar institutions that have full-time teams doing this around the clock. If you want to watch your portfolio daily that’s fine, but know that trading the portfolio daily has been shown by multiple empirical studies to diminish returns dramatically; in the meantime, what is that time worth to you? As we highlighted before, is that hour one that could earn money, spend time with friends or family, or do something you find more enjoyable? If you want to educate yourself on investing, spend the money on research software, and commit the time to be a full-time investor, please do. But if you’re not fully invested in yourself to accomplish this, don’t go chasing cat-based cryptocurrencies based on a Facebook post.

Comments 1

Pingback: This time it's different? Discussing current market events.