Nothing quite captures the attention of the American public like being wealthy. Whether it’s celebrating or decrying billionaires for traveling to space, observing major gaps in wealth between various members of the population, and otherwise simply hanging on every word (or tweet) of the ultra-successful, nothing seems to capture our attention like people with money. Yet, research over the decades has shown that the vast majority of the wealthy in the United States are relatively obscure and otherwise unseeming in the visibility (or invisibility) of their wealth. Today we’re taking some time to summarize the most significant relationships found between behaviors, decisions, and the accumulation of wealth.

The Job Matters

It’s a popular expression in finance that wealth isn’t what you earn, but rather, what you keep. Stories such as gas station attendant Ronald Read, who died with $8 million, attest to this idea. Yet, Human Capital Theory and simple common sense tell us that the investment in earning power is a significant determinant in lifetime earnings, with the average high school graduate earning only $1,304,000 in their lifetime compared to $2,268,000 for those with a bachelor’s degree or $2,671,000 for those with an advanced degree. It’s no coincidence that all nine of the professions with a median pay of $208,000 a year or more tracked by the Bureau of Labor Statistics are graduates of medical and surgical schools and that the tenth place earning a median of $207,380 per year are family medicine physicians. In fact, excluding corporate CEOs, you have to reach down to 15th place to find airline pilots as the first occupation not requiring a graduate degree for highest annual income. All of this said, the exchange of time and money in the investment of education can have a positive or negative relationship. Recently, it was reported that graduates from the Columbia University School of the Arts in film were making on average less than $40,000 a year while having average student loans in excess of $200,000. Assuming minimum payments of 10% of income over 20 years, those students will not only have paid $80,000 on their loans, but they’ll end up with a tax bill for the loan forgiveness of at least $184,119, assuming they make their monthly payments uninterrupted for 20 years. Ultimately then, the contribution of education towards building wealth is heavily reliant not only on the amount of income that education can qualify someone for, but also the cost of that education over time.

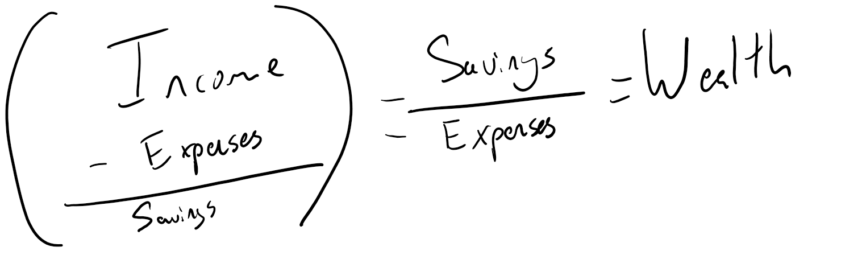

Saving Trumps Earnings

Yet, there are still many other factors that go into the accumulation of wealth. A classic example of this is the “Save for ten and stop vs. spend for ten and start” hypothetical. This hypothetical example comes in many forms but serves to illustrate the power of time and compounding interest. The example goes that if one person saved $1,000 a month for ten years at an 8% rate of return and then stopped, and a second person started saving the same amount when the first person stopped, over a period of 45 years, the first person would end up having saved $120,000 for a total return of $3,000,528.46 while the second person would have saved $420,000 and ended up with only $2,309,175. Those who build significant savings (you know, those millionaire types) rarely build up their assets as the result of a windfall event like the sale of a business or winning the lottery; rather, the vast majority of millionaires in the United States are the product of long term savings behavior compounded over years or even decades. Employment benefits such as 401(k) plans are a significant determinant, but there are also cases where we have “secret millionaires”. For example, a retiree from the Saint Vrain Valley School District who works for forty years as a teacher likely has a pension benefit through PERA that as a lump sum would be worth more than a million dollars.

Financial Independence > Social Status

An observation I often like to share with people is that some of my wealthiest clients have surprisingly humble occupations and lifestyles. One client with assets of over two million works as a waitress part-time as she transitions from a previous career into retirement. Another millionaire client has been a mechanic for the government for years. Yet, we often assume that those we see driving a brand-new Tesla or whose houses could shelter a small army are those that are doing the best. While these people may have high incomes, a high pattern of lifestyle creep and consumption often means that while their lifestyle is enviable, they are living paycheck to paycheck and often are not accumulating the resources necessary to sustain their lifestyle if they ever transition away from their current occupation. This is often a trap caused by other decisions in life; quite famously, many lawyers are miserable practicing their particular type of law, but having accumulated hundreds of thousands of dollars in law school debt, the option of pursuing areas of law that are less lucrative isn’t practical for them, and so they are trapped in a high earning, high stress, high consumption lifestyle. For those who earn financial independence earlier in life, a significant part of that formula is the decision to live well below their means, and as a result, can quickly accumulate assets. Adherents to the FIRE movement (Financial Independence Retire Early) suggest saving no less than half of your income, though this often results in a pattern of aggressively humble living, which can cause some distress later in life when the quality of life cannot adjust to a post-retirement reality of having “too much time on one’s hands.” Those who work normal length careers and build up financial resources over a lifetime often find greater levels of satisfaction in the pattern of saving that accumulates over the years.

Independence from the Bank of Mom & Dad

This point has less to do with loans for practical purposes (i.e. being gifted or borrowing money for a first-time home purchase) and more to do with a pattern of support. In their book, “The Millionaire Next Door”, Dr.’s Stanley and Danko found that one of the most significant predictors of millionaire status was whether someone received financial support from their parents after they moved out, such as a monthly stipend or annual gift. Those who receive such gifts often develop a pattern of consumption which ultimately relies on the gifts for support, such that because the adult child grows a perception that they will “always have support from mom and dad” that they never develop the financial skills necessary to build their own wealth independently. This is an important lesson not only for recipients of such gifts to consider but also a lesson for those granting such gifts to their own children. While financial support in school or during periods of distress can be a major lifeline for adult children, consistent gifts over time can have a deleterious effect on the quality of life for those growing up, as they are robbed of the opportunity to learn financial lessons on their own terms. It also goes without saying, that those who do not receive financial support after they move out, often do not change into a pattern of gifting with their own children, and thus the quality lessons of financial independence or lack thereof often pass from generation to generation.

So what is the millionaire formula?

Simply described, the average millionaire is part of a married couple, who lives in a home well below what their means can afford. The home is paid off, and the cars they drive are both well used and also paid off. They work in average to high-income occupations, and a significant number of them have engaged in entrepreneurship, which may have contributed to their affluent status. They do not own any items of jewelry or accessories worth more than $100 with the exception of family heirlooms or items like an engagement or wedding ring. In short, they do not look affluent, but they are almost certainly more affluent than their flashier peers.

Dr. Daniel M. Yerger is the President of MY Wealth Planners®, a fee-only financial planning firm serving Longmont, CO’s accomplished professionals.

Comments 1

Money for my family and my grandkids