In my newfound academic studies, I get the opportunity to read research. A lot of research. A lot of research. This isn’t for the pure fun and joy of it, but because the effort to obtain a Ph.D. is equal parts your own research and learning what’s already been done in the field. Consequently, you spend a significant amount of time learning some of the minutiae of experiments done in your field. Today, I want to bring your attention to a particular one you might find valuable in your own life.

The Study

In 2017, Dr. Danielle Winchester and Dr. Sandra Huston completed a study of variables that impacted the outcome of financial planning, with specific attention to the financial knowledge of the clients, the trust they placed in their financial advisor, and the various costs clients accrued due to the engagement with the financial advisor. Some of the findings were predictable: For example, consumers who have greater financial knowledge tend to have better financial outcomes, while those with less financial knowledge tend to have lesser outcomes. Yet, their study found one completely unpredicted outcome: That the presence of trust is a greater determinant of financial success than financial knowledge. You see, the study found that when examining the single variable of financial knowledge, knowledge had a positive impact. However, they found a contrary force that outweighed the value of financial knowledge, which was trust (or a lack thereof). You see, people who had greater financial knowledge tended to either avoid engaging with a financial advisor, didn’t follow their advice as frequently, or spent significant amounts of time “trusting but verifying” their advisor throughout their relationship. As a result, while their financial knowledge produced a premium in the relationship, it also created such a significant discount as to erase the value of their financial knowledge and actually caused them harm.

So we’re just supposed to trust blindly?

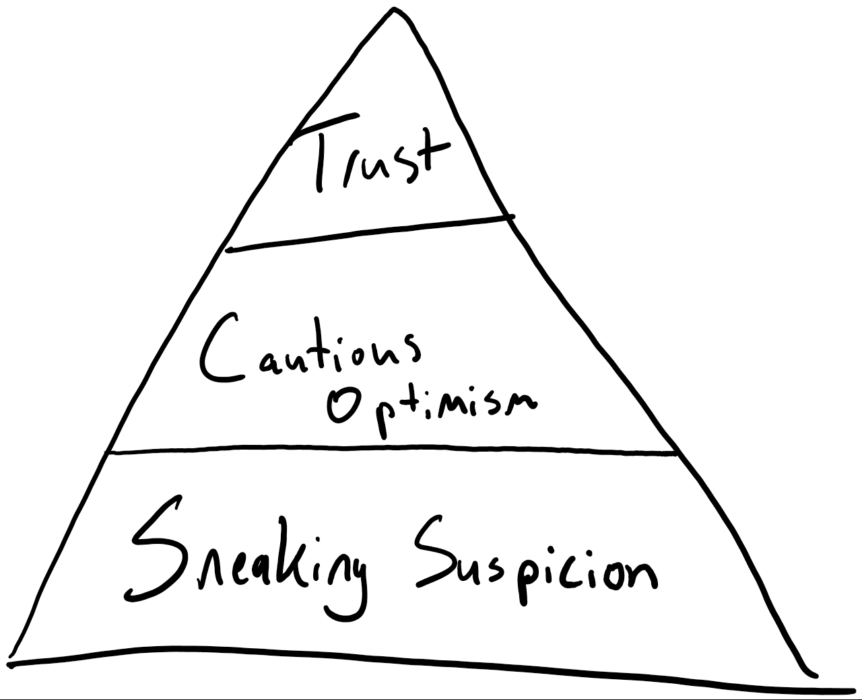

Goodness, no. You should do a significant amount of due diligence well in advance of engaging in a trusted relationship with an advisor of any kind (financial, accounting, attorney, etc.) To trust blindly is simply foolish. However, once you’ve completed your due diligence, you must carefully evaluate whether you need to continue monitoring for trustworthiness and if the cost of doing so is worthwhile compared to the value that this advisor is attempting to bring to you. For every minute spent distrusting, you might potentially be preventing yourself from being taken advantage of, but if the advisor you’ve chosen is trustworthy in the first place, that time is simply detracting from the value you receive. Preventative measures such as fiduciary oaths, clear service agreements, and reporting systems can help significantly reduce the risk of unscrupulous actors while also reducing the cost of monitoring these professionals when they help you.

Why not just do these things myself?

Well, let’s put this simply: Are you a doctor? Now, there’s a .2% chance that you are, and if you are you can just ignore me now. But if you’re part of the 99.8% of the population that isn’t a doctor, then you probably rely on doctors for most of your healthcare. You see them when you’re sick, you let them examine you for ailments and symptoms, you trust that they are making recommendations in your best interest when they say to cut back on certain foods or start taking certain prescriptions; and while you know that there are some bad doctors out there who overprescribe or recommend procedures that you don’t really need, it’s not all that often if ever that you actually seek out “a second opinion”. Because what other options are available to you? You could pretend that the stellar grades you got in biology qualify you to practice medicine, buy a medical textbook, and google furiously. Let, inevitably, you would likely come to the conclusion that you simply aren’t qualified to make medical recommendations for yourself or others. Or you could simply avoid the doctor altogether. After all, if you’re not feeling ill or pain, you must be alright, right? Ignorance is bliss, so says the old saying? Of course, there’s the true DIY-ers solution, which would be to go back to college, get a pre-medical degree, sit the MCAT, complete three years of medical school, complete a residency, and then: VOILA! You can diagnose whether you actually have a blackhead or a mole on your left shoulder. That was well worth the years of time and hundreds of thousands of dollars of education, wasn’t it?

Okay but isn’t the cost of the professional help sometimes not worth it?

When we buy material objects, the majority of what we’re paying for is the materials and logistics to get the object to us. The human time/energy/knowledge cost is separated between hundreds or thousands of units of that object a day (the author’s time for a best-selling book, the engineer who designed a flashlight, and so on). When you engage in a professional, whether that be a doctor, attorney, accountant, or financial advisor, you are paying for two things: A much more significant time commitment for your specific needs, and the amount of time and education that went into their training to do what they now do for a living. So while the cost of the professional can be high, and with that cost, a desire to “trust but verify”, the truth of the matter is that we’re probably not qualified to evaluate the service they’re providing above and beyond the results it produces. Is a hip replacement worth $50,000? That all depends on how much you value your mobility and living with less pain. Is a business contract worth paying an attorney $1,500 to draft it? That depends on the cost of having that business deal go sideways. At the end of the day, often professional services are about preventing mistakes or getting it right the first time; it can be hard to value something “going right” when it never “went wrong” due to their help, but the margin can often be enormous.

Back to the Value of Trust

To put things in perspective, the study found that the value of “knowledge” was about .1% a year, meaning that if you were a financially knowledgeable person, the value on a net worth of $500,000 is worth about $500 to you every year compared to someone without knowledge. Yet, the “lack of trust” discount is .29%, or $1,400 to that same person. For the value of their knowledge, by distrusting their advisors, they cost themselves an additional $900 a year. Over 30 years compounded, that could add up to over $90,965 at a simple rate of 7%. Yet, on the other side of the table, numerous studies have found that financial planners pay for their costs and then some. While the average cost of a financial planner is 1% of assets managed, the average planner has an investment minimum of $1 million, or $10,000 a year in fees. How is this reasonable? Well, it comes back to the measurement of value. Vanguard’s Advisor Alpha finds that advisors offer greater than 3% in net returns on assets annually, while Morningstar’s Advisor Gamma puts that value at greater than 5%. At MY Wealth Planners, we charge effectively .25% on net worth, or 1/12th – 1/20th of the value we produce. For that same financial planner average client, net of fees that amounts to anywhere from $27,500-$47,500 of added value per year, and the good news is that both the cost and value we provide scale proportionately for clients who are lower in assets or income and higher in assets and income. So the next time you’re considering working with a professional, due your due diligence ahead of time, and then trust that they’re going to help you because the value of that trust could amount to a significant sum.