It’s conventional wisdom in finance that, for those approaching or entering into retirement, a conservative portfolio is best. By “de-risking” the portfolio through a reduction in equity holdings and an increase in fixed income and cash equivalents, the portfolio’s general level of volatility (as measured by standard deviation) is expected to decline, and by mixing up the asset allocation to include fewer correlated investments, it’s anticipated that market downturns will have less of a lasting impact. Yet, there is an alternative theory and approach to retirement portfolios: a total return approach. Essentially, leaving the risk in the investment portfolio turned all the way up; or at least, not increasing the proportion of lower-risk assets.

Why would someone take a high-risk approach to retirement, a time in which financial catastrophes may be difficult or otherwise impossible to recover from? Well, simply put, it’s a belief that “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” The long-term performance of equity-heavy portfolios has traditionally trounced that of more conservative portfolios, and with good reason. The entire premise of a “risk premium” for investing in higher-risk assets, such as common stock or the funds that track them, is that while the downside can be significant, the upside is functionally unlimited. Unlike bonds or cash equivalents, where the return is largely derived from fixed interest payments on a predictable timeline, equity investments enjoy the profits of good times at the risk of loss in the bad times.

This week, we’re talking about some of the tools that can make a risk premium approach possible and a word of caution around those who overly advocate for a risk premium retirement portfolio at the client’s risk.

Hedging the Risks of the Risk Premium

Presume that upon entering retirement, you have not participated in any sort of pension or annuity program other than Social Security. For a risk premium approach to have its maximum effect (for good or ill), let’s assume you have a portfolio that is 60% US Total Stock Market and 40% International Stock Market, excluding US investments. So effectively 60% of your money is tracking the majority of publicly traded companies in the US and 40% is tracking the majority of publicly traded companies overseas. If we use Vanguard’s VTI ETF and VXUS ETF to model this performance with real products, and assume a monthly rebalance back to the original 60%-40% ratio, then this portfolio has produced an 11.72% annualized rate of return over the past decade and a 15.81% standard deviation. This means in any two-thirds of the past ten years, returns have been more than -4.09% and less than 27.53% on an annualized basis.

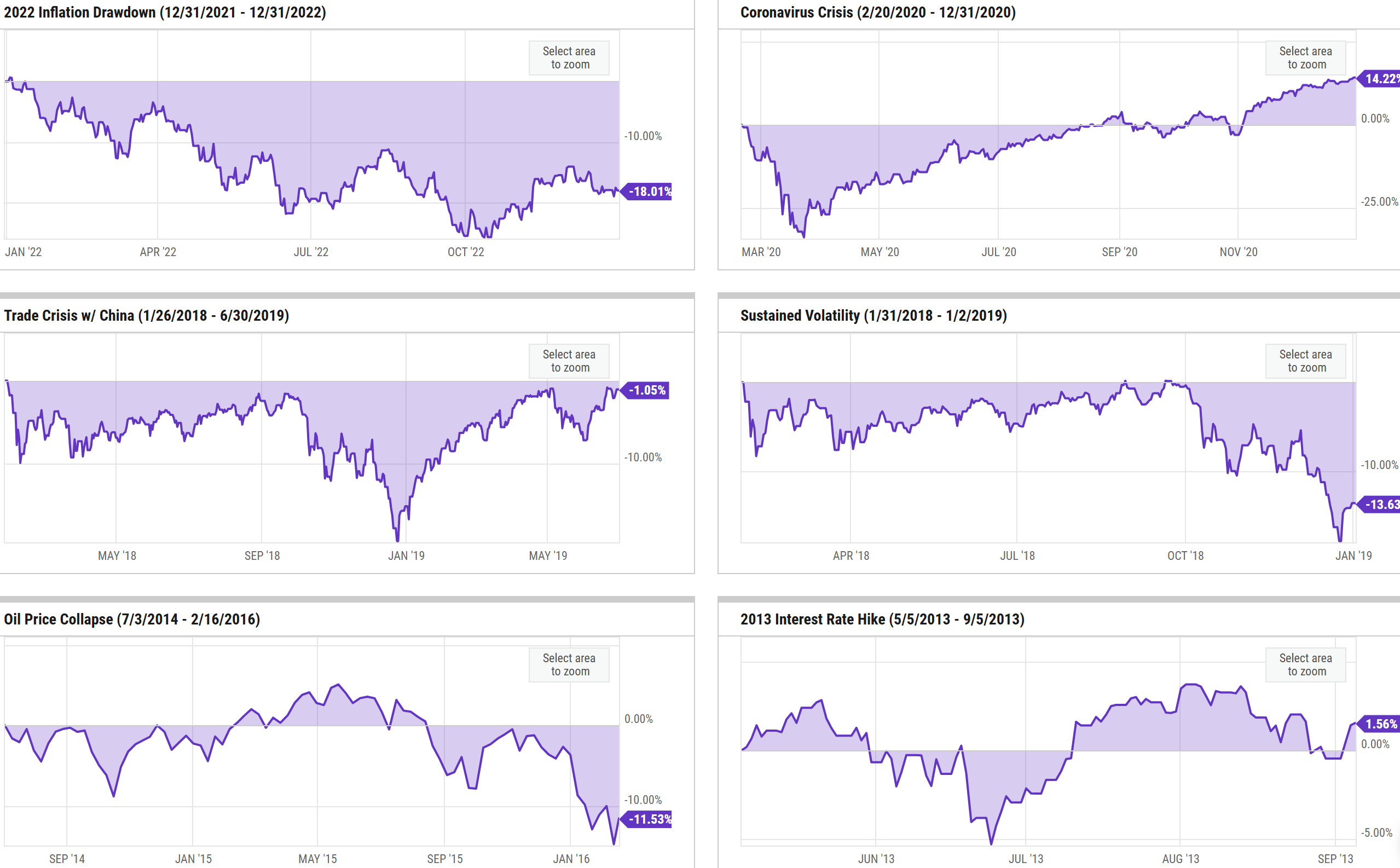

Relatively speaking, the low probability of an up to 4.09% loss might make you think this is a relatively safe bet, even if it’s volatile. But, as you can see below, major market, economic, and world events could see the portfolio lose as much as 34.05% in a month or up to 25.17% over the course of ten months.

Charts shown here were generated on 9/10/2025 using yCharts data.

Not only does the risk premium approach command better long-term expected returns, but it also demands an iron tolerance for rapid shifts in wealth! So how do we hedge against these sudden changes?

Well, the first approach involves a rather unpopular tool: a reverse mortgage. While these obtained a shady reputation in the lead up to the great recession, the earlier days of reverse mortgages involved a great many questionable sales practices and failures for those obtaining them to fully understand what they were agreeing to. Today, obtaining a reverse mortgage requires any borrower to complete an education class prior to beginning the application process.

With that in mind, a reverse mortgage can be structured either as a stream of income similar to a pension or annuity, or like a line of credit. In the case of the stream of income, this creates a defacto and ongoing hedge insofar as the necessary amount of distributions from a volatile portfolio are reduced on a going basis. The line of credit-type option presents an opportunity for a retiree to borrow money when the market is down, without any obligation to make payments during the downturn, and then return the borrowed capital when the price of securities has recovered (whether that be weeks, months, or years is an open question). In so doing, the sequence of returns risk most heavily present in a risk premium portfolio is relatively well hedged, because the retiree is not forced to sell assets at a discount during downturns, potentially running the risk of “overdrawing” on their portfolio and leaving it unable to recover.

Another option, highlighted by some excellent recent research by Derek Tharp presented at the NAPFA 2025 conference, has to do with the select timing of social security. While it’s often commonly held wisdom that retirees should just wait until 70 for social security so they can obtain the highest ongoing income, there’s a fair strategy to be applied in simply using social security claiming as a hedge against volatility. Let’s look at an example of this.

Say you retired at the age of 62. You’re eligible to claim social security but the benefit would be reduced by a substantial degree for claiming early. The markets are treating you well at the moment so you go ahead and distribute extra income that social security might otherwise pay for from your portfolio. This works well for a few years, but around the time you turn 66, the market suddenly experiences a rapid decline and your portfolio is down 40% almost overnight. While you might have an iron tolerance for volatility in the market, the problem that you’re faced with selling assets at a 40% discount doesn’t go away just because you can tolerate it. Activating social security, or any other pension or annuity option available to you, becomes a way to dramatically reduce the impact of the sudden market downturn.

By not having baked social security income into your retirement lifestyle funding to begin with, it remains a readily available and government-backed hedge against a sudden loss in portfolio value. And during the time preceding this triggering downturn, you’ve been taking money out of your portfolio at a reasonably steadily growing return, such that you likely have not only funded your retirement to date, but probably have grown the balance over time.

The final hedge we’ll discuss here is less of a tactic and more of a thing to be aware of. Many people entering retirement derisk their portfolios as we’ve already discussed. In so doing, they often put themselves at an odd place in the “efficient frontier,” a mathematical measurement of optimal risk and return that can look something like this:

Essentially, when taking the efficient frontier into account, there are optimal mixes of equity, fixed income, cash, and so on, that best align with the frontier. They’re typically not perfectly clean numbers like 50% Equity/40% Fixed Income/10% Cash, but the basic idea is less that you’re going to build a portfolio that lives perfectly on the frontier and more so that you want to avoid building portfolios that are far from it, since those will represent substantially inefficient blends of risk and reward.

We share this quick lesson on the efficient frontier to highlight that assets such as pensions, social security, and defined benefit programs as a whole, present a relatively conservative asset. When treated like a security, social security performs like a high-quality corporate bond. But depending on the level of income replacement social security is providing for you, that means it can represent a dramatic overweighting of fixed income investments in what could otherwise be a more efficiently designed portfolio. The same goes for those who are heavily invested in pension plans such as PERA, or who spend a great deal of money on fixed or immediate annuities. None of this is to say any of those investments are bad or otherwise unworthy, but that when you fail to take their substantial value into account in the construction of a retirement portfolio, something like a classic 60% equity and 40% fixed income portfolio on paper may actually be more like an 80% fixed income and a 20% equity portfolio; that alone can make it more than difficult to obtain a strong risk premium when all assets are accounted for!

Being Cautious About “Other People’s” Risk Tolerance

It has and should be highlighted that risk tolerance is an individual trait. Everyone has a varying degree of tolerance for risk, whether you define it in the academic sense that risk is measured by variation around the mean return, or whether you define it in the more common way as “[risk] of losing money.” With this in mind, while the mathematical case for a risk premium approach to retirement can make a great deal of sense on paper, it is not appropriate for all or even many people. Simply put: Money is important and while making money is exciting, studies by Kahneman, Thaler, and others have shown over the years that losing money often is far more stressful than making money feels beneficial.

This is all relevant because there are some investment management and financial firms out there, among all sorts of influencers, who regularly advocate for a risk premium approach to all investing, not just retirement savings. “VTI and chill” is a phrase out there on the internet no less than several million times; and while such platitudes an look great on paper, they ignore the very real stress that volatile assets such as an all-US-equity portfolio can create. Bear in mind, too, that the risk tolerance required to make the best of a risk premium approach also requires some comfort with hedging strategies, whether that be the reverse mortgage or social security claiming strategies highlighted above, or simply being willing to “go without” for a time in retirement due to not wanting to sell assets on the downturns.

None of those concerns or risks matter to an investment firm that makes money from client assets come the good times or the bad; worse, companies, generally speaking, do not have a “time horizon” they need to be concerned with in the same way retirees do (e.g., time until retirement, time in retirement, and so on). Companies are, generally speaking, some sort of immortal. Thus, so long as they have sufficient capital reserves or access to credit, they can weather a volatile aggregate client portfolio mix moreso than the individuals living on their life savings can. Thus, the risk premium is even more attractive to an investment management firm; to say nothing of the common difference in many product costs as well, wherein equity funds are often more expensive than fixed income funds, for those firms that both sell investment products and the management services that select them.

None of this is to scare you off of a risk premium approach, but to recognize that both you as the investor need to have substantial risk tolerance to follow it through to its best qualities, but also that you may be pressured by those with less to lose than you to engage in such strategies when it would otherwise be uncomfortable to you.

Dr. Daniel M. Yerger is the President of MY Wealth Planners®, a fee-only financial planning firm serving Longmont, CO’s accomplished professionals.

Comments 1

Pingback: A Case Study in Bad Planning - When Brokers "Plan"