I’ve spilled a good amount of digital ink over the past several years about the pointlessness of debating fees in the world of financial planning. Not because fees are irrelevant or unimportant in the measurement of the cost of financial products or services, but because the debate is typically either people with a financial interest in arguing for or against one model or another, or, even more typically, the debate about cost entirely ignores its incredibly important partner, value. That is to say, succinctly, that arguing about costs while ignoring what the costs are paying for is, frankly, stupid.

It’s been my great joy not to get sucked into the fee debate for the better part of four years now since I published my last blog on the subject back in 2022. But recently, many colleagues have pushed forth excitedly an example of a “good” fee debate for me to watch, saying that the parties really made their cases quite well. So, with some trepidation, I waded in. And an hour later, I’m annoyed that I gave it the time. However, as I listened to the particular debate in question, it occurred to me that while the tone and tenor of the discussion was about as good as anyone might hope for, there really was a good opportunity to use this particular case study as an example of why even well-intended and seemingly better-informed parties often muck up the whole discussion and leave their audience less informed than they began.

So, this week we’re dissecting the recent “Bigger Pockets Money” debate on “AUM vs Flat Fee,” and using it as a case study in why most people arguing about fees really have no idea how or what they’re arguing for. And for those readers not in the world of professional finance, this is a good look into why, when your opinionated brother-in-law starts going on about why no one needs a financial advisor or why anyone can do their own finances without help, no matter the circumstances, they’re really just telling you they occupy a summer home on Dunning Kruger hill.

Before We Get Into It

Let’s give credit where credit is due. None of the participants in the debate was an amateur in the area of finance, and the tone and tenor of the conversation, as I noted above, were about as good as they could have been (with one little exception at the very end after the debate was over). I will say, before I rake the transcript over the coals, that I wish more debates and discussions on the subject of the business of finance were carried out in such a generally congenial and warm tone. Never mind that a good bit of what was discussed was nonsense, I can at least appreciate that all parties were respectful and polite in the discussion, and never wandered into the ad hominem territory that is so typical of the discourse on financial services fee models.

With that said, let me lay the groundwork for how I’m going to discuss the podcast. Rather than posting an hour-long transcript for you to read and then commenting or red-lining, I’m just going to pull out the salient timestamps and quotes of interest and then provide my commentary on the issues therein. Any cutting of dialogue before or after any given quote isn’t an attempt to play gotcha (there’s no point, I’ll link to the relevant moment anyway), but just to try to keep the word count down and the issues in what was said as the central point.

And finally, I’ll just give the polite caveat now: I understand that it’s easy for me to sit here and armchair quarterback what was by all appearances a live debate. So please know that I recognize the unfair advantage I have in being able to relitigate something with all the time in the world to do so, but please also know that I have no malice toward the participants in doing so, and that I’d happily share a beer with Mindy, Scott, or Ryan.

Issue One

Scott (0:00:21): “I’m super excited about today’s episode. A few weeks ago I put out this post to my LinkedIn feed. I said: “Hello, Mindy and I are looking for two financial planners to justify their compensation models in the Bigger Pockets Money podcast. We feel very strongly that flat fee or advice only, which means no AUM and no commissions, is the best way to align interest between a CFP and their clients, but we’d like to hear the case argued by a CFP who charges an AUM fee and about why their compensation model is not the conflict of interest we feel it to be.”

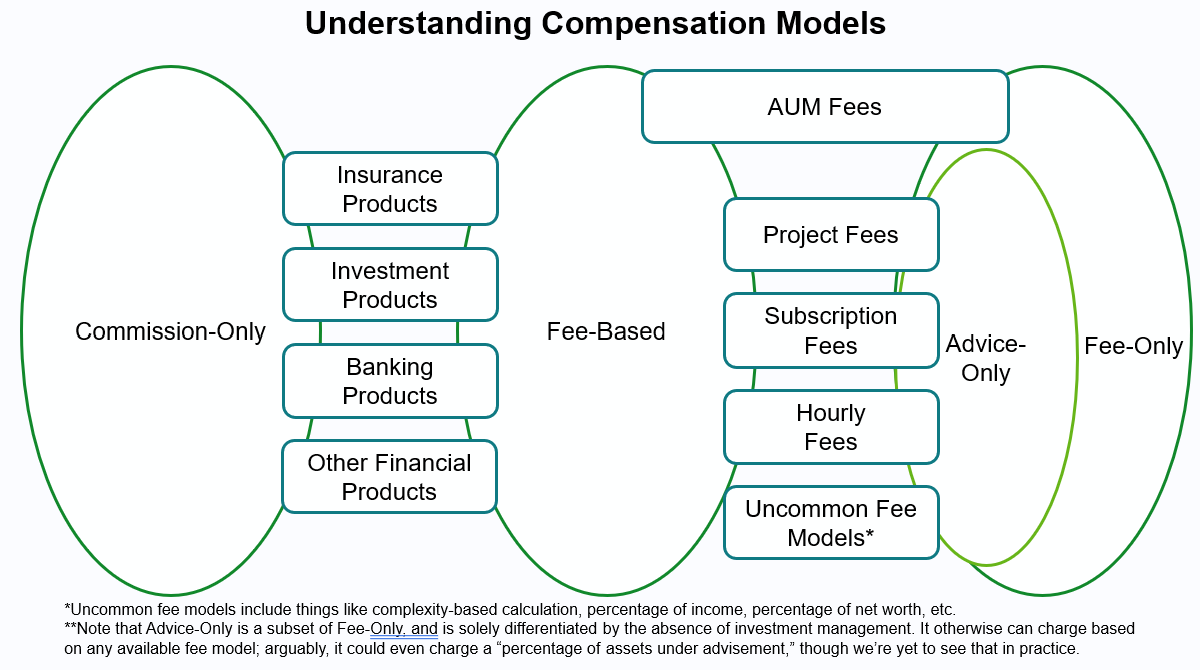

Right at the outset, the debate is framed around a false dichotomy and poorly defined terms. Scott presents both a specific fee model and a range of fee models as interchangeable, saying that “flat fee or advice only, which means no AUM and no commissions.” This is conflating a specific type of fee model, “Flat Fee,” with the larger umbrella term of “Advice Only.” Flat Fees can be charged by advice-only, fee-only, and fee-based financial advisors. When I worked for Waddell & Reed, for example, we charged a “flat fee” for financial planning as a project-based engagement that could take a few weeks or as long as six months. We then might, as a fee-based firm at the time, also offer investment management under an assets under management model or have sold investment or insurance products after the fact as a result of the needs and issues identified as part of the financial planning process.

In turn, advice-only is an umbrella term, similar but not mutually exclusive to the terms fee-only or fee-based. Advice-only planners can offer services on an hourly model, project model, or subscription model. They may use the same fee for everyone, complexity factors such as household composition or types of planning issues identified, or other metrics such as income or net worth, to provide a calculation of what then becomes a fee charged on an hourly, project, or subscription basis. While an advice-only planner wouldn’t sell investment or insurance products on commission, their more specific feature is that they explicitly will not manage investments for clients, thus “advice-only.” This does not preclude a flat fee advisor under any of the common compensation models from managing investments for their clients, nor are all flat-fee advisors (as noted above) going to forgo the sale of investment or insurance products, as flat-fee advisors can be fee-based.

All of this gets wrapped up into the complexity of the fact that many financial planners and financial planning firms elect to bundle their services under one fee structure, and others elect to unbundle their services. Thus, you may also see one subscription-based financial planner charge a flat ongoing fee for services that include investment management but not the sale of investment and insurance products, who might fairly be called “fee-only”, but another might charge a flat ongoing fee for services that does not include investment management or the sale of investments or insurance products who could fairly be called both “fee-only” and “advice-only.” Yet notably, though one might provide more services, that may not inherently mean that they charge more or less than one who provides fewer services.

The quote then wraps up by calling out AUM as “the conflict of interest we feel it to be.” This is problematic because no service model of any kind is free of conflicts of interest. Yet, by framing the debate around the conflict of interest presented by AUM, and setting the bar on Scott & Mindy’s feelings about the model, the debate effectively starts on poor footing. For anyone who participated in Public Forum or Lincoln Douglas debates back in high school, the proper framing of a debate contention for an issue like this could be better framed as: “The AUM fee model’s conflicts of interest are greater than those in a [flat-fee or advice-only] service model.” For the proposition, Scott & Mindy, opposing the proposition, Ryan.

Unfortunately, this false framing haunts the entire debate from front to back, as they go on to discuss these models and regularly and inaccurately interchange the terminology in question.

Issue Two

Scott (0:08:39): “The mechanisms of monetizing financial planning services, the way I bucket them, are, one, hourly or project-based advice which would be in the bucket of advice-only. You pay someone, you know, an hourly rate and they give you advice for whatever it is that you’re asking about or you pay them a project fee. The second is essentially a subscription or an annual contract. This is what we call flat-fee financial planning. Often the range of $2,500 to $7,500, can get a little higher depending on the complexity of the situation. And that’s going to be a full-service financial planning. It’s going to include the things you just said there, financial planning, it’s going to include coaching, it’s going to include investment management optionally in some cases. The third mechanism for monetizing financial planning services is assets under management fees. Those fees typically are charged for the investments that are actually managed by the adviser, and they can range from 0.25% so you know, $2,500 on a million dollar portfolio a year to uh as much as 10, you know, 1% or even more; so that could be from $2,500 in this example to $10,000 a year on a million dollars in assets under management, and that will scale with portfolio size. That’s what we’re going to be discussing today. The fourth way that these services are monetized is with commissions. So commissions can be paid to the financial adviser for selling investment or insurance products. So for example, if someone takes out an expensive whole life insurance policy, the adviser could make tens of thousands of dollars in commissions for originating that policy and get an annuity on an ongoing basis for as long as premiums are paid. And then that brings us like the last two structures here are hybrids that include forms, you know, various forms of these. So fee only is commonly used to describe a model where that you do as Nerd Wallet; an AUM only model or in some cases can describe an AUM plus some kind of flat fee or some kind of hourly based compensation for other work there. And then the last model is going to be what we call fee-based. This is also a hybrid structure and fee based basically means that the adviser can do everything right they have all these mechanisms they can charge by the hour if they want to they can charge flat fees on an annual basis they can charge commissions and they can charge AUM but I think it’s likely common that a fee-based model overwhelmingly is dominated financially with revenue form commissions and AUM fees. Do you agree with the way I’ve kind of framed the discussion for mechanisms of monetization in the financial planning industry?”

Ryan (0:11:05): “Yeah, absolutely, spot on.”

But no, not absolutely spot on! Not absolutely spot on at all! By laying out compensation models with the already identified definitional mish-mash noted in Issue One, this framework treats umbrella terminology as intermixed with the actual fee models, and in turn, intermixes them with the service models involved. Compare how Scott describes the models above with this Venn Diagram that actually clarifies the terminology:

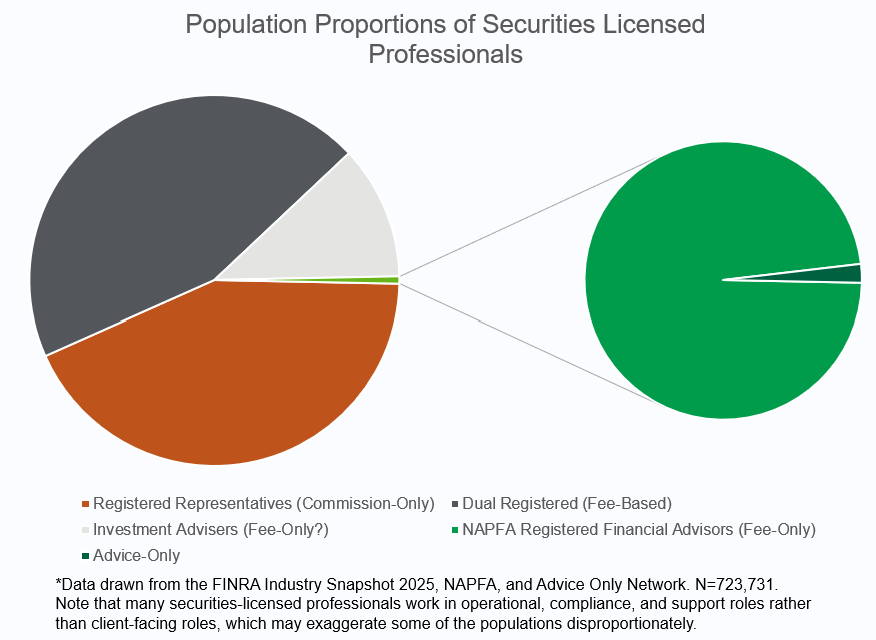

But further, while Scott wraps up by describing the bulk of revenue in the fee-based world as being derived from AUM fees and commission-based sales, that doesn’t get at the half of how skewed the dichotomy. While the prior diagram might suggest that the populations of advisors are reasonably proportional, the truth is that the industry is far from such proportionality. If we try to put the industry terms above to scale by head count, the world looks much more like this:

Proportionally speaking, the diagram above is far from perfect. As the disclaimer notes, FINRA and the SEC do not differentiate licensed professionals between those who are client-facing and those who work on the “back office” side of the financial services industry. It is also difficult to say that those securities licensed professionals who are only registered as investment advisers are fee-only or fee-based, as many financial advisors do not hold a Series 6 or 7 brokerage license but do hold their Series 65 or 66 Investment Adviser Representative license and an insurance license, which would classify them as fee-based rather than fee-only. We can only really confirm an understated population of approximately 4,500 NAPFA Registered Financial Advisors as being validated as fee-only financial planners, and a sample population of 100 advisors registered with Advice Only Network as being advice-only, which in turn may cannibalize from each other in industry representation terms as many NAPFA registered financial advisors are advice-only and many advice-only financial advisors are NAPFA members. Even if we assume these populations are understated by a factor of 10, and there are actually 45,000 fee-only financial planners and 1,000 advice-only financial planners, this would make the entire collective about 13.6% of the available financial advice professionals in the United States. But other studies have approximated that fee-only financial professionals sit around 1.4%-2% of the total financial advisor population, so it seems far more likely that there are genuinely only a few thousand professionals in either of these models at the present time.

Why does any of that matter? Because in laying out the assorted fee and compensation models as Scott does and Ryan agrees creates a false perception that there’s a healthy number of all of these models available to the public, when the fact is that Scott is actually understating how dominant commissions and AUM models are in the industry. Being fee-based doesn’t immediately mean an advisor is going to use AUM as their fee model for financial planning, but even a cursory review of the ADV Part 2s for the largest fee-based firms in the industry (names like Merrill, Morgan Stanley, Wells Fargo, UBS, LPL, Raymond James, Cetera, Edward Jones, etc.) shows that the vast majority of their fee-based offerings are in fact AUM-based. In turn, the number of firms offering hourly, subscription, or project planning on a fee-only basis or advice-only basis is a minority and a minority within a minority.

Issue Three

Ryan (0:11:15): “Look, historically, I’ve always stayed away from selling products. And it, you know, it feels like all of the different fee structures, that one has the biggest conflicts of interest embedded inside of it. I would wholeheartedly agree that I would stay away from one of those where someone is selling you products, they’re earning a big commission. You just have to question what the incentives are.”

Mindy (0:11:37): “That has historically been my anti-CFP stance, anti-financial planner stance in general, is I don’t know why they’re going to be recommending these things to me. Is this just going to be a really great product for me or is this a really great product for their pocketbook?”

Here’s the first instance where the general cordiality of the conversation deprives the “debate” of a really material point. Ryan goes on to suggest that Mindy’s aversion is really just an aversion to whole life insurance sales and that Mindy is just mentally conflating CFP® Professionals with insurance salespeople. While that point is fine, it leaves a much better point laying out there in the open. For example:

“Mindy, you’re a podcaster for a platform that is entirely oriented towards a DIY audience that considers itself financially savvy or otherwise is becoming financially savvy by enjoying your educational content. You’re telling me you and your audience have all the self-efficacy to do most if not all the things a financial planner could do for them, but simultaneously that they couldn’t just ask for the “why” behind a planner’s recommendations? They couldn’t read the disclosure documents and service agreements? Ask them for written explanations and further disclosures of their conflicts of interest and the rationale behind the plans they provide? Have them sign a fiduciary oath or ensure one is included in their services agreement? Throw it all in AI and ask it to call out red flags or areas of concern to clarify before moving forward?”

This irreconcilable false dichotomy of “people don’t need” or “people only need/only should” flows through the debate and is never materially challenged, and it’s frankly, exasperating, particularly when Mindy goes on to fully admit she should have engaged a financial planner years ago.

Mindy (0:13:00): “And I should clarify I meant historically. You know many years ago when I first started investing, ‘oh why would I have somebody else do this I can do this myself’ and I think there’s a lot of people who in our audience had the same thoughts in the past. And now I’m moving towards, hey, I do think I need some professional advice. I think that I could have benefitted from some professional advice 20 years ago when I was having babies and would have perhaps saved more for my kids’ college than I did, which is currently zero, and she’s in college right now.”

Issue Four

Scott (0:20:05): “I would love to bring you my top three concerns with the AUM model and we can react to them one by one here. The three primary concerns I got are, one, especially as portfolios scale, I think this is an extremely expensive way to pay for financial planning. Two, I believe while there’s no conflict free or perfect way to compensate anyone, that the flat fee or advice only model produces less conflicts of interest or fewer uh conflicts of interest than the AUM-based model. And I think the third one is that the automatic passive deduction of fees from investment portfolios removes transparency and the hard re-evaluation of service…”

Two vague generalizations and one outright false statement? Let’s look at these in the order presented.

The first argument is that it’s extremely expensive. But “extremely expensive” is a subjective statement that is absent of value or otherwise presupposes a lack of value. To give an example, if I tell you a mystery car is $100,000, we could agree that $100,000 is objectively expensive for a car. But if I then go on to tell you that the car is a 1955 Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR “Ulenhaut Coupe,” which last sold at auction in 2022 for $142 million, you’d trip over yourself to come up with the cash to buy it (even if only to resell it and pocket a cool $139.9 million before taxes). The argument that it’s expensive exists in a vacuum when what the cost is paying for goes completely unaddressed, and this problem is well addressed by basic economic theory, marginal utility theory, and financial planner-client interaction theory. People generally do not buy or consistently buy things for more than they are worth absent deception or fraud, but the argument being made here isn’t that AUM is fraud, just that it’s “extremely expensive.”

The second argument is that flat fee or advice-only models produce fewer conflicts of interest than the AUM model. Setting aside the definitional issues that we’ve already addressed, let’s ask two questions: One, since the claim is that there are fewer (“less”) conflicts of interest in a flat fee arrangement than the AUM arrangement, what is the quantifiable number of conflicts of interest, and two, is the number of conflicts versus the magnitude of conflicts the most relevant measurement of the problem being highlighted here? There is a single conflict of interest the AUM model has that another model doesn’t: “The financial advisor is incentivized to make recommendations that increase their assets under management and to otherwise avoid recommendations that decrease their assets under management.” In practice, this means there are obvious conflicts of interest to recommend investing instead of paying down debt, not spending or gifting money “excessively,” and to avoid recommending investments for which assets under management cannot be billed (like real estate, the core asset class at the heart of the BiggerPockets Money audience), and to otherwise engage in ongoing services rather than one-time or short-term services.

But does that mean a flat-fee service provider has no unique conflicts of interest? Well, it depends on the nature of the flat fee (one-time project, subscription, hourly, or otherwise). For example, a one-time project planner is incentivized to limit the duration of the engagement, cut corners on the work they provide, or to otherwise expedite the completion of the project. A subscription-based provider is incentivized to add as many subscription-based clients as they can possibly service and to underserve or reduce the time spent on each client relationship as much as possible, minimizing effort while maximizing revenue. An hourly planner is incentivized to read and write slowly, think about things for protracted periods of time, conduct research when it may not be strictly necessary, or otherwise to protract the length of an engagement in order to increase the hours spent on the project while not necessarily increasing the value delivered. And whether the service provider is using one of these fee models and is also managing investments and is thus merely fee-only or is not managing investments and thus could be called advice-only doesn’t impact this much, other than potentially making a client relationship “stickier” than it otherwise would (a conflict not unique to the AUM fee model, but to the service of investment management in general across any fee model!) And of course, none of this is to say that any provider under any model may engage in additional conflicts of interest that aren’t intrinsic to their model, whether by ill intent or ignorance on their part; that is to say, some of the conflicts of interest present in one model may be present in another if only because of the intentions or incompetence of those offering services within it.

So quantifiably, does the AUM model intrinsically have more conflicts of interest than flat fee models or an advice-only offering? No. It merely has different conflicts of interest, and thus the argument about the magnitude of the conflicts seems much more relevant than the quantity of conflicts. If the AUM-conflicted advisor recommends you sell your real estate portfolio to buy a diversified stock portfolio, is that intrinsically bad advice? Not necessarily, because it depends on the totality of the facts and circumstances leading to that recommendation. In turn, if an hourly planner suggests you buy as many properties as possible to “diversify” your real estate portfolio, while inadvertently also increasing the time required to properly provide financial advice and planning around each of those individual properties, was that too intrinsically bad advice? Not necessarily, because again, it depends upon the totality of the facts and circumstances leading to that recommendation. How does Advice A align with Goal A, Advice B align with Goal B, and so on?

Finally, third, the simply inaccurate statement that investment management fees somehow remove transparency. I can tell you, having looked at investment account statements from every major brokerage in the United States and some minor ones, I’ve never encountered a brokerage statement that did not clearly show either the investment management fees or commission ticket charges taken from an investment account. This is both because it’s required by regulations, but also because clients can do basic arithmetic. If the account statement shows a balance of X at the start of the statement period and a balance of Y at the end of the statement period, and the collective addition and subtraction of gains and losses didn’t add up to the difference between X and Y because the fees or commissions were somehow missing from the statement, there’d be class action law suits from here to the end of the horizon. Further, all of these commissions and fees are disclosed in writing to clients of investment advisers on investment accounts. In the case of commissions on other products, such as life insurance, they’re typically baked into the policy and less transparent, but the argument here was about the “problem” with AUM, not the broader issue of compensation transparency.

Now, are there potentially substantial conflicts of interest buried inside investment management accounts? Certainly. Advisors affiliated with an investment or insurance product firm may be financially incentivized to recommend their firm’s products and services over others. But that’s not unique to AUM, that issue can exist in a firm with any type of compensation model that is commission-only or fee-based. Further, the firms under the commission-only and fee-based models might receive revenue-sharing incentives, payments for shelf space in the firm’s “recommended” catalog of products, or otherwise provide sales incentives to the representatives (e.g., vacations, cars, etc.). These are all abhorrent conflicts of interest, but again, they are not unique to the AUM fee structure specifically, albeit they are far more common within those compensation structures.

Issue Five

Note, the following transcript is much easier to follow if you watch the linked portion of the debate video on YouTube and see the graph he’s showing in tandem with these statements.

Scott (0:21:11): “We’re going to say how much does financial planning services cost under two scenarios. Flat fee versus AUM using Nerd Wallet Wealth Partners fee schedule which has a graduated fee schedule where if you’re going to pay .9% on your first $500,000. I think I did actually graduate this so you’re going to be a little cheaper than our model here is going to show. That’ll bump down to .8% once you get into the $500,000 to a million range, .7% when you get in the million to $2.5 million range, 6% on 2.5 to 5 and so on and so forth. We’re going to apply a real return to portfolio balances and then add $20,000 per year because this is BiggerPockets Money and our users are going to save about $20,000 per year probably at minimum. And we’re going to say which one is more expensive, flat fee or AUM based. And so again, these are the this is the graph of those projects here where we say a flat fee is going to cost $7,500 per year. We have this escalating with inflation. So these are all real dollars. The retainer goes up by two and a half a year um every year stays constant in 2026 and if we assume that we’re going to pay $225,500 over 30 years for financial planning advice in this scenario and the AUM fees are going to compound although the slope will change as we get into higher and higher total AUM fees until we get to really big differences depending on the starting balance we have or the total amount of wealth we have. A kind of table way to summarize this is if we start with a $500,000 portfolio, we’re going to pay $330,000 in fees for the same financial planning services as our $7,500 a year flat fee model. If we start with a million bucks, we’re going to pay $520,000 which is nearly double the amount we’re going to pay for flat fee. If we start with $2 million, we’re going to pay $865,000 or about $600,000 more in fees for the same financial planning services over a 30-year period. And I also want to caveat this that I think I was actually very generous to the AUM model here because it’s very unlikely that the $200,000 or $500,000 or maybe even the million dollar portfolio individual is going to start their relationship with a flat fee adviser at $7,500 a year. They probably start much lower.”

Holy straw man, Batman! Now, it’s not to say that a hypothetical scenario like this is entirely unreasonable, but we have to remember that this was billed as a debate, and as such, some basic things need to be recognized. First, the assumptions visible in the video and loosely explained in the transcript set up a losing scenario out of the gate. For those not able to see the video, the stated assumptions were:

- All dollars: 2026 dollars (real) – meaning that they would be shown in 2026 present value terms rather than inflated

- Time horizon: 30 years

- Real return: 4.5% annually

- Annual contribution: $20,000 in 2026 dollars every year

- Fees: Tiered marginal AUM schedule, applied annually and deducted from assets

Stated in a different spot:

- The AUM fee schedule would be based on the Nerd Wallet fee schedule.

- The flat fee provider would bill at $7,500 annually, increasing for inflation at 2.5%.

- Estimates of cost would be based on the AUM starting out at $200,000, $500,000, $1,000,000, and $2,000,000

The snuck assumptions were:

- The services for the AUM provider and the flat fee provider are identical.

- Inflation is 2.5% (appended to the flat fee provider’s fee increase)

- That the flat fee provider will only increase fees on a non-stochastic linear 2.5% inflation rate, despite the highly improbable nature of this in practice (more on this later)

The final results shown were:

|

Fee Structure |

Total Fees Paid over 30 Years in Present Value |

| AUM starting with $500,000 | $330,152 |

| AUM starting with $1 million | $520,582 |

| AUM starting with $2 million | $865,456 |

| Flat Fee – $7,500 |

$225,000 |

*Yes, $250,000 is missing because the graph showed it would cost less than the $7,500 flat fee model.

So, we can’t blame Ryan for not being able to pause the debate to take the 30 minutes to build out an Excel model to compare assumptions and results, but we can highlight the characteristics of what makes this a straw man hypothetical, and why Ryan probably should have dismissed it out of hand rather than conceding politely to it.

First, we’re repeating the mistake of comparing things solely on cost rather than value. The straw man presents the services offered for $225,000 as being identical to the services offered for a cumulative $865,456, which is a debate-winning snuck premise to get your opponent to concede to. To illustrate the basic flaw of this premise, let us present an equally absurd application of this snuck assumption: “Jeff Bezos would happily trade his family office in for a single financial planner charging $7,500 a year.” It doesn’t take a genius to immediately call out that Jeff Bezos likely spends millions, if not tens of millions, on the services his family office provides for him, but that the team of experts required to manage Jeff’s financial plan and assets is almost unrecognizably different from a hypothetical individual financial planner’s suite of services.

Consequently, we have to draw attention to the extremes a flat fee planner versus a higher cost planner is going to warrant. While $7,500 is a perfectly reasonable fee on a flat fee basis for many mass-affluent Americans, and many bargain-seeking consumers will happily pay $7,500 instead of 1% on $2 million if they can, in fact, get the same services, the issue is that while you can certainly find anecdotal examples of this happening, we need to point back at the number of advice-only and fee-only planners noted above in our pie chart to the number of commission-only or fee-based advisors out there. The majority, if not almost all fee-only and advice-only planners offering a flat fee service to those with multi-millions in investable assets, are doing so largely in a lifestyle practice. There are perhaps a thousand or two thousand of these planners out there, and they’re great planners. But there are not several hundred thousand of them, and certainly not enough to serve the entire population demanding financial planning services.

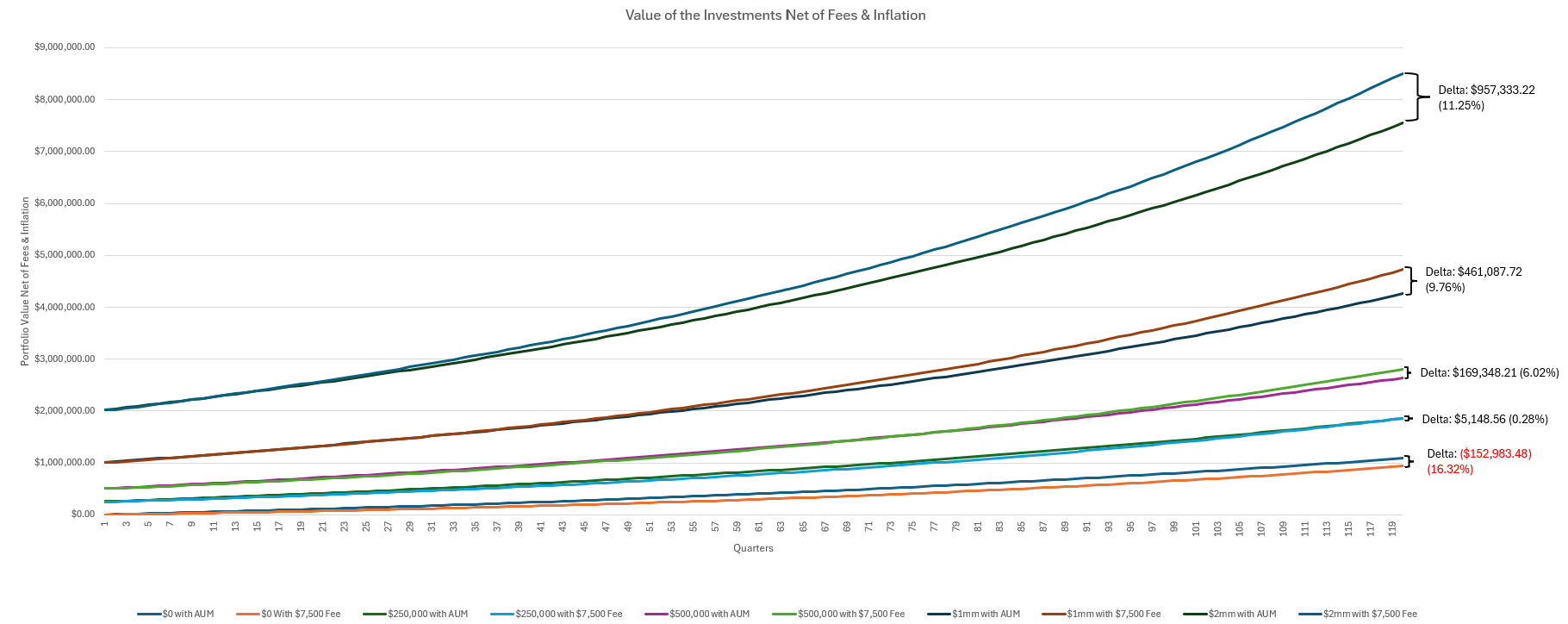

Second, with the snuck premise of identical services out of the way, the focus on solely cost ignores the relative value in question. By discounting everything back into present value, taking inflation out of the represented model, and then saying that one fee increases by a real rate of 0% while the other increases at 4.5%, you’re stacking the deck at the outset. This is made no more clearer than by the absence of a “starting with $0” AUM hypothetical and the missing results of the $250,000 starting AUM example that ended up costing less than the $7,500 example presented in the chart in the video. So why not discuss the spectrum of value in question? Let’s take the same set of assumptions, but instead, look at the variation in end results. Spoilers, it will still come out favoring the flat fee model, but it helps us compare the costs to the value. Also, we’re going to apply Nerd Wallet’s fee schedule correctly (billed quarterly in arrears, not annually), because we can do the math correctly. And we’ll throw in the missing $0 starting balance result while we’re at it.

To adjust for the gross rate of return assumed in the model, we have to reverse engineer the real rate of return of 4.5% back from the 2.5% inflation rate presented in the assumptions. This is 7.1125% gross return, which, once adjusted for inflation, is 4.5%. But this ignores the impact of the appropriate fees as well. With Nerd Wallet’s fee schedule on display, the net-of-fees-and-inflation adjusted rate of return is not 4.5%, but incrementally is 3.5904%, 3.6907%, 3.7912%, 3.8919%, 3.9927%, and 4.0938% as it reaches marginal breakpoints. With these datapoints known, we can calculate the results of the fee models in the assumptions, as well as the $0 case.

Now, you might look at that chart and say, “Aren’t you making Scott’s point for him? There’s almost a million-dollar gap over 30 years if you started with $2 million dollars!” That’s entirely fair, dear reader, but let’s contemplate two specific points that this highlights:

First, while Scott presented the difference in costs between the $250,000 starter and the $2 million starter as being essentially a 4x differential, we see that the end result gap is only 11.25% after 30 years in the case of the $2 million dollar case and is 0.28% in the $250,000 case. And of course, the gap is favorable for the AUM model with the otherwise missing $0 starting case. Those gaps aren’t negligible, but in the span of 30 year this unfavorably pre-supposes geometric returns without stochastic randomness, that is to say, “generally linear growth” of the portfolios and fees rather than the actual changes, in which sequence of returns risk would play a material role. Notably then, the fact that the AUM fee can increase or decline with market changes provides it a nominal advantage over an equal or greater static fixed fee in such volatile market conditions, but to show that we’d be getting really out into the weeds.

Second, to return to the incredibly important snuck premise of the “identical services,” let us now examine what else is missing from Scott’s model: What the fees are spent on. The industry norm for distribution of revenue is 40%-50% spent on direct expenses (the staff who deliver financial advice), 30% on overhead (rent, software, etc.), and 20%-30% in margin (profits, which in the AUM model will expand and contract with the market cycle and growth of the practice). Importantly, this means that the snuck premise of identical services suffers from a fatal flaw: The flat fee model is presupposed to only increase costs at the rate of inflation, but the cost of skilled professional staff and financial services technology certainly do not map cleanly onto the national average rate of inflation. For example, one of our core software platforms (that clients see as the “performance reporting portal”) increased just this month on a year over year basis by 61.1%, going from $9,000 annually to $14,500. Staffing costs have increased by an annualized average of 5.27% annually over the past five years. Rent has literally more than doubled in the past two years (albeit some of that comes from our expansion, but an expansion demanded by the growth of the practice!) All of that to say that the AUM firm would not only have substantially more revenue in almost all of the comparisons presented to absorb these costs and changes, but that they could also afford to provide excess and premium services where a flat fee model given the generous assumption of growing only by inflation could not remain as competitive long term; it is also anecdotally noteworthy that of the flat fee financial advisors I know, none of them have increased their flat fee solely by inflation that I’m aware of; and whether you view this as a “base flat and excess AUM” or a “base AUM or discounted flat fee” really doesn’t change the nature of the problem.

Issue Six

Ryan (0:25:44): “My hypothesis was that most people are going to benefit from the flat fee option. That was my hypothesis and that’s what I went kind of strongest to the hoop with. And the interesting thing when I kind of looked at this 2 years later is that the clients that were having the best outcomes were clients who were being charged the AUM. That was true for clients that started with $100,000. That was true of clients who started with $2 million. And the reason being is that the flat fee model, we were doing a financial plan, we were getting everything in place, everybody felt really good about it. And then things kind of, I don’t want to say they got on autopilot, but often they kind of due. And in year two, people say “Hey that was great. I’m really happy with this plan that you built, but I don’t think I need to pay the $3,000 or $5,000 for next year because If feel good with everything.” And then you check in six months later and you say:

“How’s everything going?”

“Well, an election was coming up and I got really nervous and I sold everything. Or you know, there was, you know, a bump in the road, the market was down, you know, 10%, I panicked and I sold.”

While I’m sympathetic to the point Ryan is trying to make here, particularly as a firm that only offers ongoing services and not one-time project services, I have to bury my head in my hands with frustration. Because the argument Ryan is making here is not in favor of AUM as a form of compensation, but an argument for ongoing service and investment management services. It doesn’t matter if the client pays a flat fee for those services, hourly for those services, a subscription for those services, or a percentage of their annual expenditures on dog food. What matters is that the client is consistently supported and guided, and has mechanisms and safeguards to help ensure they don’t make a big mistake when markets get scary or when the implementation of investment strategies needs to stay consistent over time. But Ryan is unable to make the argument separating AUM from the service model because he’s looking at this issue solely through the lens of his firm’s business model, which apparently suffers from retention issues on the delivery of services for the firm’s flat-fee business. Sigh.

Issue Seven

Scott (0:42:03): “I got this argument a lot on my LinkedIn post from financial planners, especially of the, you know, some of the folks that are of the ilk that I kind of had stereotyped in my mind if I kind of got some of the folks that I was expecting to get kind of coming in real hot on this. But there was this concept of, “I’m an AUM” or “I’m a fee-based guy” and “I’m really good at financial planning and these other guys that are charging flat fee or advice, they’re like discount planners, they’re not good at this.”

A rather specific claim, so I went and took a look at the post in question and read the 173 comments to date. While some advisors were in the comments making an argument for AUM, it was never based on “I’m really good at planning” or based on flat fee advisors being discount advisors relative to AUM advisors.

I saw arguments for investment specialists saying that they charge akin to investment products because they’re functionally offering an investment product rather than a wealth management or planning product. I saw others arguing that its easier for billing and more tax efficient in the case of pre-tax retirement accounts, or that it’s otherwise a better alignment of incentives between the advisor and clients who have a goal of investment wealth maximization. I saw some pointing out (as we saw above) that AUM can literally be more affordable for those starting with low investment balances or who otherwise don’t have ample free cash flow.

But, as I pointed out above, I did not see anyone claim that their AUM model was justified because they were superior or that the flat fee model was a poor substitute or otherwise inferior (one commenter questioned the premise of the snuck premise). It’s possible that one of the two commenters who have me blocked on LinkedIn made such arguments (it would be in character for one of them but not the other), but I can’t imagine why Scott would otherwise make this entirely falsifiable argument in good faith or why Ryan would let it slip by. That’s not to fault Ryan for not reading all 100+ comments on the original post in preparation for the debate, but merely to point out that, as a financial planner, you just generally don’t hear this type of claim ever being made by your peers because of the compliance rules around such a claim. Saying “I guarantee my fees are worth it because I outperform sufficiently to warrant them” is akin to ringing a regulator’s dinner bell and signing yourself up to pay an enormous fine in the not-so-distant future, and I can’t imagine how that wouldn’t highlight the obvious falsity of Scott’s claim that there were “a lot” of people making the argument he’s claiming they were.

Issue Eight

Scott (0:50:26): “But it seems like in the last year in particular as folks have gotten, you know, smart or knowledgeable or educated about the fees that are being charged in the space, that a huge cottage industry of small firms are starting to pop up that are charging these flat fees and that the assertion, the light assertion you’re making that it’s harder relatively to find those is less true and is getting less true all the time and that there are an abundance of quality flat fee financial planners who will manage assets and who will make a great living, you know, at $7,500 bucks, a couple dozen or maybe up to 100 clients doing that. They’ll make a great living and begin taking market share from the AUM mode. What’s your reaction to that school of thought?”

Ryan (0:51:08): “That might be true. And I think like any industry, things evolve. I think about how the broker was replaced by more of this advisory model. There has been and there will continue to be fee compression. There’s no question about that.”

As noted above, Scott’s claim here is both true and false. While there have been a few thousand firms that have emerged through the auspices of institutions like XY Planning Network that aim to provide services under a different service model than just AUM, in the same timespan that a single brokerage firm, Edward Jones, has added over five thousand financial advisors, with nothing to say of the headcounts at Merrill, Morgan, UBS, Wells Fargo, Raymond James, LPL, and others.

But Ryan then goes on to not only concede to the idea that flat fee firms are taking a noticeable amount of market share from AUM firms, but that fee compression has already been happening in financial advisory firms and is going to continue to happen. Yet there is not a single study I’m aware of that would back this statement. The XYPN Benchmarking Study has shown every year since its inception that not only do 100% of new firms increase their fees within the first three years of their establishment, but that the trendline of average fees for financial planning in all flat fee, hourly, and subscription fee models has gone up over time, not down. The Schwab RIA Benchmarking study, which goes back decades at this point, has never reported material decreases in the AUM fees charged by firms for any trend or reason other than that they tend to discount as the assets under management creep into the multiples of millions. Where the claim could be true is that investment product fees have gone through fee compression (e.g., mutual fund expense ratios are down substantially over the past few decades), but that’s not the same thing as professional service providers undergoing fee compression.

And the probability that service providers are going to undergo fee compression in the not-so-distant future is highly improbable in a world where the most recent studies by McKinsey and Cerulli suggest the United States will be short by 75,000-100,000 financial planning professionals to meet public demand by the mid-2030s. But both the blanket acceptance of Scott’s fiction about an abundance of flat fee providers and the unnecessary false concession that fee compression is occurring in the financial advice industry by Ryan would almost make you think he was a plant and not a real and invested debater for his side of the argument by this point.

This Wasn’t a Debate

By the end of this discussion, and that’s really what it was, it’s pretty clear that this wasn’t a debate. Scott presents multiple straw men, and Ryan accepts them at face value, then kindly concedes that Scott is probably right about anything he’s said and offers a non-sequitur for his own argument or makes factually incorrect statements. I said at the outset of this rather long article that the cordiality and politeness of this discussion were ideal in the sense that too many debates become ad hominem slinging or shouting matches. But the problem with the format of this “great debate” everyone has been telling me about is that in the interest of being polite in the course of the discussion, one of the participants seems to have forgotten that the point of a debate is not to convince your opponent that they’re wrong, but to sway the audience to your side of the argument.

While by the end of the debate Mindy (who hardly participates in the whole thing) says she’s otherwise had her eyes opened a bit and she’s warmer to the idea of AUM advisors, Scott ends up essentially declaring victory; or at least, saying that Ryan has failed to meet the bar by which his feelings on the subject of AUM could otherwise be changed. And that’s no surprise, to be frank, because as I’ve just said, this wasn’t a debate, it was a polite discussion.

I have no doubt that Ryan genuinely believes in the value of the AUM model and is happy running a financial advisory firm that offers services within that compensation structure. But this returns to the crux of my well-established position: debating about fees is stupid. Not simply because of the arguments I’ve made before on the subject, but also because most of the people debating about fees frankly aren’t good at debating.

As I said up top, I don’t have any hard feelings or malice for Mindy, Scott, or Ryan, and I’d happily have this discussion with any of them or buy any of them a beer for the pleasure of their company (Mindy, we’re actually here in Longmont with you, so feel free to stop by. We’re on top of Cave Girl Coffee in the Prospect neighborhood.) But frankly, none of them should be signing up for a debate about advisor compensation, and their audience is less well-informed for having listened to them try.

Dr. Daniel M. Yerger is the President of MY Wealth Planners®, a fee-only financial planning firm serving Longmont, CO’s accomplished professionals.